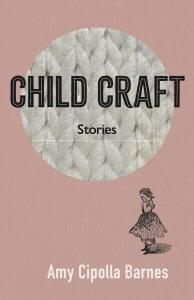

Fragile connections and haunted nostalgia wend a graceful path through Child Craft (Belle Point Press, 2023), the latest collection from Amy Cipolla Barnes. Raw with memory, Barnes adds a dreamy earthiness to writing infused with surrealism, the everyday retold with an off kilter spin. Barnes offers brief snapshots of deceptively nondescript lives, enlivened by the intrinsic oddness of normal existence. I spoke to Amy about how the collection came together.

Fragile connections and haunted nostalgia wend a graceful path through Child Craft (Belle Point Press, 2023), the latest collection from Amy Cipolla Barnes. Raw with memory, Barnes adds a dreamy earthiness to writing infused with surrealism, the everyday retold with an off kilter spin. Barnes offers brief snapshots of deceptively nondescript lives, enlivened by the intrinsic oddness of normal existence. I spoke to Amy about how the collection came together.

Rebecca Gransden: Child Craft embraces the hybrid form. What does hybridity mean to you, and how is it implemented regarding this collection?

Amy Cipolla Barnes: For this collection, hybrid means a mix of essays, CNF, micro fictions and flash fiction. I also like to push the boundaries further and combine genres, blurring the lines even within individual pieces. Some of the included stories have a news story that is true at their core or a childhood story, but they then veer into fictional territory.

RG: While the collection ranges, it is also remarkably cohesive. How did you go about the selection process when it came to determining which pieces to include?

ACB: I actually start that selection process as I write/submit each individual piece, staying within general themes. In the case of this collection, I’ve also played a bit with the idea of the Childcraft volumes. Some of the titles within that book series where the title is inspired by are Poems of Early Childhood, Narrative Poems and Creative Verse, Tales and Legends, Guidance of the Child, Holidays and Famous People, and Nature Excursions. While I didn’t create chapters or pigeonhole the stories and essays into those headers, I did envision the collection as falling into categories. The collection is in a loosely-linear form; there are also smaller groupings within the order that echo the Childcraft volumes. For example, the retail and photography studio story series of flashes and the lost child series.

RG: Over what timespan were the pieces included in the collection written? Were they always intended to be gathered together, or did their identity as a collection evolve over time?

ACB: These flashes, essays and micros were mostly written in two years proceeding, mainly because my earlier stories are in the previous collections. There are some older stories included and some unpublished ones that lingered stubbornly in Google Docs before I added them. Additionally, the essays and CNF included are a little older because my previous collections were labeled as fiction only; opening up this collection as a hybrid one enabled me to add in those CNF pieces and essays that didn’t fit in the earlier, fiction-only collections. I honestly wasn’t expecting to gather enough stories and essays to create another collection, but was very happy when they fell into place together.

RG: Are the pieces autobiographical? Whatever the answer, is that a question that even matters?

ACB: Some are, but I purposefully haven’t specified which are and aren’t. I think the question matters but I’m not sure if it’s important to reader, editor, author – maybe mostly just to my mother. I also tend to always include some autobiographical material in most stories, intentionally or not. There are some essays within the collection that are obviously (at least to me) autobiographical but even then, I’ve changed or omitted details in most places.

ACB: Some are, but I purposefully haven’t specified which are and aren’t. I think the question matters but I’m not sure if it’s important to reader, editor, author – maybe mostly just to my mother. I also tend to always include some autobiographical material in most stories, intentionally or not. There are some essays within the collection that are obviously (at least to me) autobiographical but even then, I’ve changed or omitted details in most places.

It might be simply human nature to write the things that we know autobiographically or are part of our surroundings – maybe a little nurture and nature? Maybe this is a new kind of auto-maybe autobiographical fiction. For practical purposes, the collection has the more broad “stories” label on its cover and not the maybe-more-accurate “stories, essays, and creative non-fiction.”

As examples, I was never stolen as a child and my mother isn’t an alcoholic; if anything she’s a self-proclaimed teetotaller. However, I did have other relatives who were heavy drinkers with heavy consequences. I did get lost in a mall and had the fear of being stolen laid out every day – even as I left the house on my bike alone for hours. Some of that fear was rooted in news stories of the day, like the children being kidnapped in Atlanta. The stories that feel autobiographical, that really aren’t, may have at their root common childhood fears rooted in some truth.

RG: “Women in Jane Fonda thongs and sweaty terry-cloth headbands and wristbands are wrapped in seaweed and plastic wrap until their middles disappear. Like magic. In the space of a commercial. We realize there’s magic in our kitchens. Saran Wrap magic.” A theme that consistently recurs is the way in which strangeness inhabits ordinary lives. Everyday items take on magical potential and meaning is found in the gathering of the plainest details of day-to-day living. Your pieces capture the oddness at the heart of much of existence. What does normalcy mean to you and how do you go about addressing it in your work?

ACB: I’m not sure I’m the best person to define “normalcy.” I’ve never quite fit in a societal box, even doing what I thought were expected things – graduate school, go to college, get married, have kids, raise kids, get kids off to college (my current defining placeholder). In my writing, I think that I use “normal” things as markers too and then I toss in the unexpected, which is like life, but my fictional unexpected things are a little more off the wall. In that vein, I use pop culture references – like Jane Fonda, 80s workout gear, and Saran Wrap – to ground the stories while then stretching the time/space/people to be less normal, less expected.

As a kid, I was always making something out of other things. Tools gone missing for Rube Goldberg machines. Pastel toilet paper turned into paper dolls. Handwritten newsletter filled with fanciful goings-on.  Going back to the collection’s title, the Childcraft books I read were a road map that encouraged that creativity. Looking at my Child Craft stories with this question’s context, I think/hope there is a strong play on that return to a more magical childhood time, with a series of books to lead play and exploration.

Going back to the collection’s title, the Childcraft books I read were a road map that encouraged that creativity. Looking at my Child Craft stories with this question’s context, I think/hope there is a strong play on that return to a more magical childhood time, with a series of books to lead play and exploration.

RG: Many of the pieces contain aspects of light surreality, such as in “Dental Molding,” where the protagonist describes being born with a renowned “mouthful of teeth,” or “The Side Show of Birth,” featuring an unusually lengthy newborn. What attracts you to the surreal and what about it lends itself to your subjects?

ACB: I pull some of my story ideas from odd news stories which then turn into surreal elements in my fiction; those stories are often so unbelievable they lend themselves to storytelling. I’m fascinated with old-timey circuses and unique people in general. I’ve mostly written in an American South fiction genre and that form feels ripe for the surreal, curious, or odd – even in small areas. All balanced with enough believability and reality to keep readers reading and guessing.

One of my favorite short stories by Flannery O’Connor is “Good Country People,” which features a man whose prosthetic leg is stolen. While not overtly surreal, it is a story that feels like it couldn’t/shouldn’t happen in real life, but in that way it is interesting. In that same vein, I’ve been drawn to stories about women who sleep next to their dead husbands, encounter the Nephilim, sleep overnight in a museum, get hit by a bus in the opening paragraph, and wear their wedding dress to mourn a failed relationship. I’m currently carrying around a story idea about a real life person who got arrested in small town after small town for illegally selling encyclopedias in the 1960s.

I think everyone has surreal qualities but we might forget or ignore them in adulthood; Child Craft is my attempt at bringing some of that surreality and imagination of childhood back to adult readers (and maybe kids too).

RG: Religion and superstitious or spiritual belief return as themes throughout the collection. Could you elaborate on this aspect?

ACB: Each of those things came into play in my own childhood. I was exposed to a patchwork of different churches and religions. In my earlier collections, I explore a little more of the darker side of those experiences with a story on faking stigmata as a child. This may be the area that I most place with the surreal or unbelievable because those experiences were puzzling to me as a child and maybe most affect me as an adult.

RG: Many of the pieces are centered on mundane or liminal locations — the family home, the local neighborhood, small-town surroundings with familiar markers like fast food places and factories. Could you talk about the sense of place you apply to the pieces featured in Child Craft? Where did you grow up, and what aspects of the environment in which you were raised have the most influence on the collection?

ACB: Most of my childhood was spent in the Midwest and Texas with my adult years in Southern states. With a plea for forgiveness to current Midwesterners, there is something mundane and peaceful surrounding the Midwestern states. Western Kansas. The plains. Fields of sunflowers, wheat and corn. Frigid winters. Unbearably hot summers. Tornadoes that destroy towns without thoughts. The familiarity of those places and the landmarks, like restaurants and factories and silos, are built into my DNA. A little hardscrabble. More small town. While the Midwest may feel like mile marker after mile marker, there is still a feeling of community. An immigrant melting pot of German foods and farmers. Foods that I still crave today but that are so hyper-regional that I can’t find them again.

ACB: Most of my childhood was spent in the Midwest and Texas with my adult years in Southern states. With a plea for forgiveness to current Midwesterners, there is something mundane and peaceful surrounding the Midwestern states. Western Kansas. The plains. Fields of sunflowers, wheat and corn. Frigid winters. Unbearably hot summers. Tornadoes that destroy towns without thoughts. The familiarity of those places and the landmarks, like restaurants and factories and silos, are built into my DNA. A little hardscrabble. More small town. While the Midwest may feel like mile marker after mile marker, there is still a feeling of community. An immigrant melting pot of German foods and farmers. Foods that I still crave today but that are so hyper-regional that I can’t find them again.

While I find myself either rhapsodizing or cursing the Midwest as a place, it is also where my childhood was. Where neighbors handed warm zucchini bread over fences, a 10-year-old drove me around a farm in a rusty truck, and I most likely met a serial killer. All of that influenced my childhood and adulthood, crafted how I see and approach life. In that way, I write a sense of place into my stories because I remember them, but I’m also searching for it. In defining “place” in my stories with pop culture and time markers, I’m trying to impact that to readers too even if they had a completely different experience with the same things, a shared and unique nostalgia.

RG: The pieces don’t shy away from the harshness of life, and themes of neglect, sadness, the melancholy undercurrents of suburban life, and resilience, all feature. Many of the pieces skillfully imply a greater tragedy playing out in the lives of those you represent. On several occasions I had the sense that events were one step away from emergency, lives lived under the looming threat of uncertainty. What is it that draws you to these themes, and how do you approach incorporating them into your work?

ACB: This is an interesting and appreciated observation about my stories; I hadn’t thought of it that way but it feels right. While these are collections instead of a novel, I think I might have been attempting to do worldbuilding within each story and in aggregate, like little chapters of these characters’ lives even if they aren’t overtly living in the same space. A neighborhood of stories and characters.

RG: The issue of familial ties is central to the collection as a whole. The potential confusion and disquiet of motherhood features strongly, as does family breakdown and estrangement. Many of the pieces suggest strained connections and dysfunction. Looking back on the collection, how do you view it in retrospect?

ACB: I view it as exactly that. While my own familial relationships may be fraught at any given time, I have yet to meet anyone who doesn’t have some level of breakdown or estrangement in their family. The aunt that no one sees. The brother who is in prison. The grandmother who drinks in her kitchen out of a mason jar. Motherhood itself is disquieting and confusing – I have two adult kids now and I still don’t know if I’m doing it right. In that way, this collection is full circle. I have a mother. I was a child. I am a mother. All of the experiences along the way (and these stories) are part of the journey.

RG: There is an unsentimental nostalgia to the collection, as you portray the mixed emotions of passing through stages of development and into adulthood, the bittersweet nature of witnessing markers of the passage of time. I found the use of corporate goods to signify stages of growing up particularly true. Certain brands that were only available for a limited time do evoke specific eras strongly, and to a certain extent we can measure life in relation to the items we buy (or had bought for us), the fast food places we frequent, or the TV or media we consume. Are there examples of any of the above that trigger a powerful nostalgic response for you personally, or perhaps an example from the collection that stands out?

ACB: I’m feeling particularly nostalgic these days with both kids off to college. I have so many pop culture placeholders that make me feel nostalgia, and a bit of an obsession for dying/dead malls/label-scarred stores. Those stores and restaurants that defined my childhood when I didn’t realize they were. In that way, I wish I had today’s instant technology to record some of those places and their signs. A lot of my nostalgic moments involve food and while I don’t always give my flash characters names or clothing details, I do find myself feeding them and taking them shopping. That may be a side effect of writing shorter pieces; I rely on pop culture nostalgia to define the characters and their backdrops. And that happens especially in this collection because it is more childhood-based.

ACB: I’m feeling particularly nostalgic these days with both kids off to college. I have so many pop culture placeholders that make me feel nostalgia, and a bit of an obsession for dying/dead malls/label-scarred stores. Those stores and restaurants that defined my childhood when I didn’t realize they were. In that way, I wish I had today’s instant technology to record some of those places and their signs. A lot of my nostalgic moments involve food and while I don’t always give my flash characters names or clothing details, I do find myself feeding them and taking them shopping. That may be a side effect of writing shorter pieces; I rely on pop culture nostalgia to define the characters and their backdrops. And that happens especially in this collection because it is more childhood-based.

My Instagram feed is full of old commercials and signage. Some of the items that trigger memories: Holidomes, Oldsmobile Cutlasses, Farrell’s Ice Cream, green stamps, gas station glasses, Montgomery Ward, Woolco and Woolworth’s, old-style Kmarts with cafes and early Little Caesars, music, piano and bookstores in malls, Dairy Queen on my way home from school, bierock drive-thrus, Taco Tico, Pizza Inn, Pipe Organ Pizza, Godfather’s Pizza with a “godfather” roaming the restaurant, TG&Y, 1970s shoe stores, oldschool McDonald’s with a play yard or a stagecoach in the middle. It’s not enough to just mention these places and things, though; my process is to try and include enough sensory details to help readers more fully remember.

The nostalgia is sometimes more for the experience or the place, not the surrounding childhood, even when my childhood looked idyllic. In that way, each of the pop culture or nostalgic backdrops represents a happy moment, which hopefully serves to soften some of the harsher or tough topics in the stories, just as it may have done in real-life childhoods.

However, in a weird way, a lot of places and things are surreal as an adult. Going to McDonalds isn’t a “treat” for my kids like it was for me. I eat Brussels sprouts as an adult and love them. During the pandemic, I made Lil’ Smokies cooked in cherry pie filling. The combo does not taste anything like I remembered. By writing the nostalgia from an unreliable child narrator POV, my goal is to preserve some of that “that tasted good to me when I was 6.”

RG: With the collection ready to release and hand over to those who want to read it, do you have any thoughts or expectations regarding it? What would you hope a reader take away from it?

ACB: Having a book ready to launch brings new meaning to that word “launch” for me. I have an image of shooting my book out of a book-shaped t-shirt cannon at unsuspecting sports fans. I don’t want that to happen, but in the same way, I would love to have people that I don’t “know” in the writing community find and read my book. Someone who doesn’t know what flash fiction is. Someone who usually reads in a different genre entirely.

ACB: Having a book ready to launch brings new meaning to that word “launch” for me. I have an image of shooting my book out of a book-shaped t-shirt cannon at unsuspecting sports fans. I don’t want that to happen, but in the same way, I would love to have people that I don’t “know” in the writing community find and read my book. Someone who doesn’t know what flash fiction is. Someone who usually reads in a different genre entirely.

What do I want readers to take away from the collection? I want them to take away what they find in the stories, whether that’s a shared pop culture experience or a surreal take on something less positive. I want that to happen in an individual way. Someone said they read my stories more than once to understand or figure them out. While I’m not trying to be obtuse or to make people read more than once, I do love the idea of people reading and re-reading my writing.

In writing the individual pieces and creating a collection, I’ve only done half of the work so far. The harder part for me is promoting and selling. I would give away all the books at no cost if I could. My first two collections were both during pandemic days with printer delays and other issues that plagued books of all kinds in 2020 and 2021 and they still were able to reach growing audiences. There will be a launch for this book and I’m ready for all the wonderful things in its future. As long as it isn’t launched into a sports stadium.

Read “Divorced” and “Tuesday at the Monastery” from X-R-A-Y’s archives.