IN LOVING STRANGLEHOLD by Brecht De Poortere

Mosi is Sprite, Banji is Coca Cola. Whoever loses, does the rounds to check for hippos that might have strayed too far.

Mosi is Sprite, Banji is Coca Cola. Whoever loses, does the rounds to check for hippos that might have strayed too far.

What’s it like to die? To stop being. Gone in a moment, carried away on the wind. Does it hurt?

How a mother could be so? Why when she’s in the same room with me I feel swallowed up by a heavy coat pulling me down?

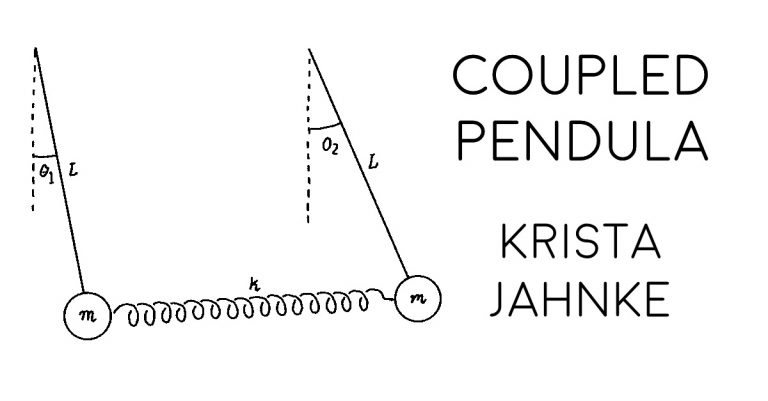

We had sex, he took my blood. Positive ions, positive feedback loops. The cycle perpetuates itself.

Tamberlyn fell on the pavement, hard. Her body slapped against it. It sounded like someone dropped a lot of meat.

On my way out of the closet I noticed a trunk at the edge of the bed… An antique padlock hooked through the clasp, but it was unlatched, so I slid it out and opened the trunk.

She hits the button to go live and slowly eats something. It could be anything: an apple, a banana, a small granola bar. Comments fly in, encouraging her.

Since I met MOLI she has of course been my vital thing.

How sad is to witness the deflection of someone from your own ethnicity, who breathes the same air, eats the same dishes, but is enemy to your land’s ethos?

The plague, the Good Prophet told them, was a judgment, and it would lay Harpers to waste if they did not repent, so they begged the Lord for mercy.