Sometimes I catch Greta sniffing the glass door after hours. I’m only tempted in the mornings, want that clean, thin scent before the chlorine does my head in. But you’ve gotta stride on through, resist the glass. Get paid.

Each morning my first task is feeding the animals their vitamins. The pills look like croutons, spongy loofah bread. I snuck one in my mouth once to check the texture, to make sure it wasn’t too rough for their sweet pink gums. They’d suffered enough.

Cleaning animals of oil is a lengthy process. It requires lengthy training. Not just anyone can go out and save oiled wildlife. Greta trained me, but all I can remember from that day is the joke she made: hope these shoes don’t make my dogs bark. She meant the seals.

The animals are collected and sorted (live, dead) at a different facility, where staff make sure they’re fed, rested, stable, ready to be cleaned. I’ll take a light eyelid nap at work to that image: them huddled and warm, safe; though I know the reality is oil, oil everywhere. Then they come here to be cleaned. There’s a whole separate area here for cleaning them in tubs, like in those Dawn ads, a rubber-gloved hand giving a baby duck a bath. That’s what I thought I’d be doing when I signed up. Research shows these animals can no longer reproduce, that they’re infertile now, and god, do I know about that. I get called into the Dawn room to organize the different-sized tubs, but that’s as close as I get to the gasoline, plugging my nose. I haul the XL bin behind the bleachers of our pool for emergency naps when the chlorine makes me feel lazy.

The animals come to our rooms once they’re clean, our shallow pools their temporary housing. Here they get to play. It’s like working at a zoo, I imagine, but better—you know they’re going home. I’ll think too long and hard about that, that they’re actually re-released somewhere they don’t recognize. That they might miss their home so much they’d rather drown. When I feel that way I’ll call two states over, to my brother. One day he called me back and said we lost the house. Our family house, the one he’s gone broke over, fixing up after the storm.

Lor, can you go into another room to talk?

Floyd, I’m not in a room, I’m in a lake.

I don’t remember what I really said to him, just that I was in a wetsuit feeding a dolphin peanut butter when he called, that I pressed end; the water line rippling against the pool wall, my own damp ghost.

Greta is great at cheering me up. She says, look at these cutie patootie animals, going for a dip! And she’s right. Nothing fixes you up like a bird taking a bath, the sweet vibrations of its wings, all clean. I’m addicted to Visine, the kind called tears, they’re good for your eyes I guess, or for when you need to disguise your crying.

Today my doctor told me there is an upside to missed periods: you end up saving your eggs. If you don’t ovulate, they don’t drop.

But are they any good?

We use the pool lanes to group the animals when we get bored, birds with big beaks, little quackers, and turtles in the shallow end. The big boys in the deep. Right now we have three dolphins, one manageable whale. We like to speak into our hands, like they’re microphones, report on the spill: we are in the process of un-spilling all the oil. The animals are very very clean.

I’m close with these two sea otters, Bubble and Squeak. Or rather, by naming them and telling other people I named them, I’ve tied them to me. They spill and splash water everywhere, all over. But I understand, I tell Greta, wouldn’t you splash like that if you knew someone was coming right behind you to clean it all up? I wrap towels over their heads, let them waddle around like E.T.

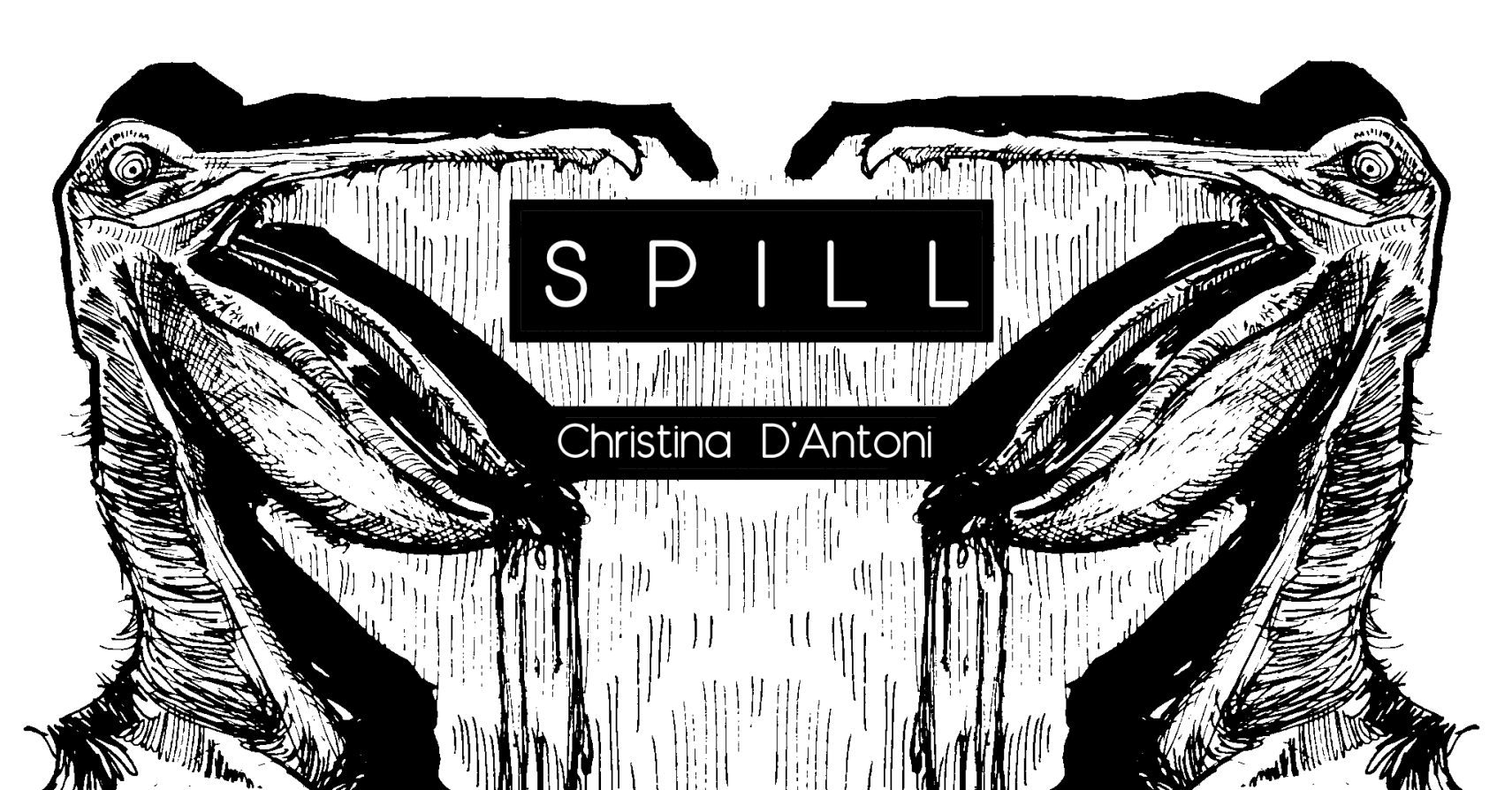

I finally complained about the chlorine to my manager, and he said there was no chlorine in the pool, that the animals would die in those conditions. That it was a residual smell, from the complex’s past as a swim club. He looked at me, an idiot, wanting to end. I spent the day cupping the treated water into my hands, sniffing it, offering it back to the pelicans. Splashing it fatly into my eyes.

I was so set on the toxicity of gasoline, big bad oil—I forgot that anything else could hurt.

That week I developed congestion I felt tightly in my ears. Only there. I lost my eyedrops after that, scoured my place for them, checked the animals, their teeth and cheeks. I noticed the lids stopped fitting on my water tumblers, my earring posts stopped snapping into their backs. I was scared of what would go off next.

At night I dreamt of pelicans strung up in the oaks by their beaks, choked in Spanish moss, the storm’s winds blowing them down. Cars sliding through gasoline, smearing their bodies into the street.

I didn’t tell Greta about the dreams, the drops, the lids, the backs, about not knowing the pool was void of chlorine. I wanted to blame it on her training, but that only led back to blaming myself, for not listening to her, for thinking rehoming oil-slicked birds would rehome me.

I didn’t trust her any less, but something was shifting wildly in me, too dark for her, for Bubble and Squeak. It was painful, holding it in, feeling it rise in different parts of me.

I tried forcing myself to tell her. She was playing a game with the seals, her voice in her fist, HONK if you’re lonely! The seals honked back. I couldn’t laugh without my ears hurting, the hurting keeping me further removed from her, still. I felt my chest lift, a breeze that felt like relief, like normalcy soaring back, but it was one single, spraying sneeze. It smelled like the liquid death long stored in my body, eking its drip up and out of me—all oil. I had a sudden craving for clean, cold glass.