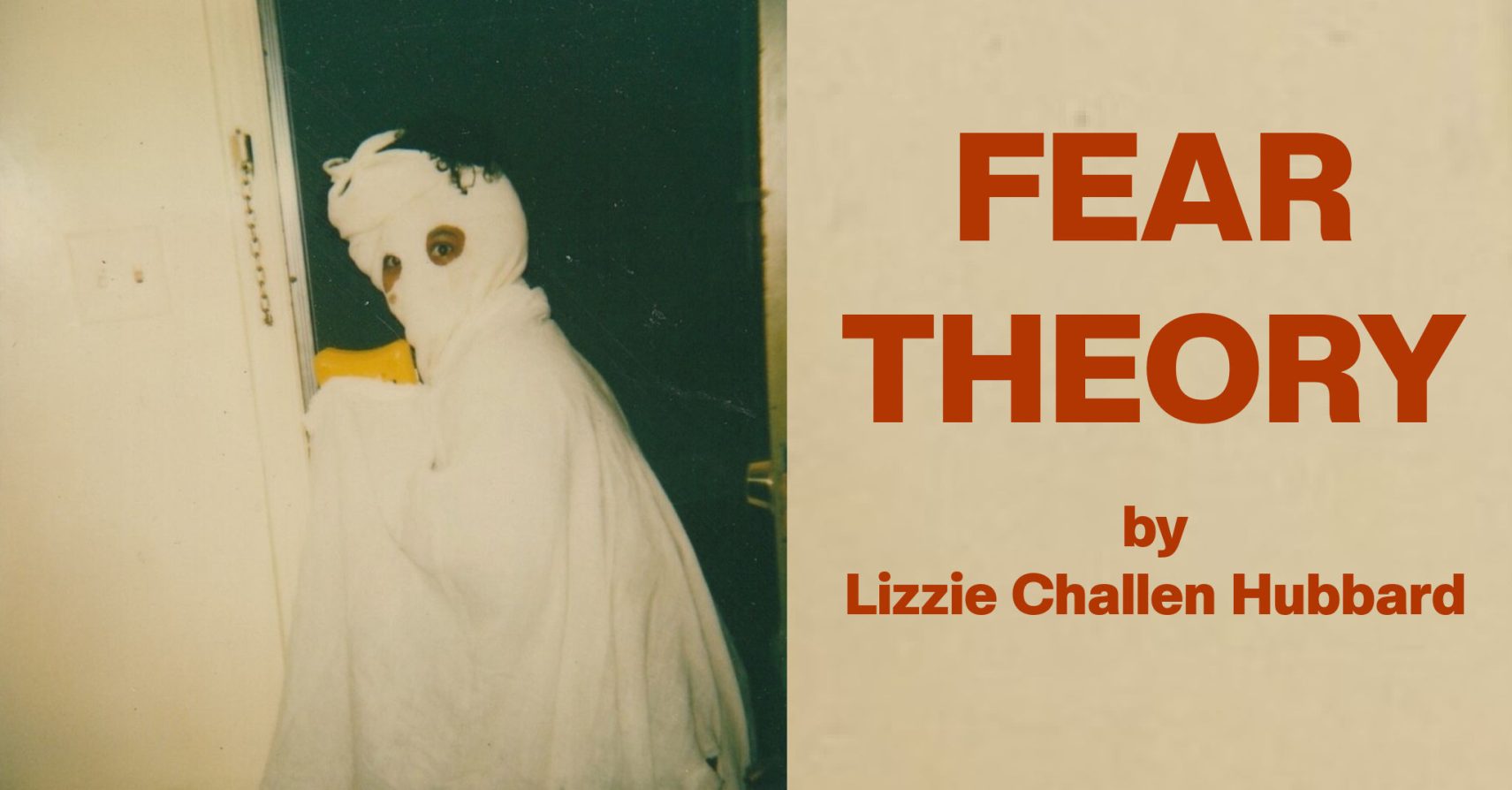

FEAR THEORY by Lizzie Challen Hubbard

Everything I know about love I learnt working weekend shifts on the Ghost Train. It was a sweet gig for a 15 year-old — sitting in the mucky perspex booth, trading tokens for screams. We opened after the sun went down, when the kids from nearby villages would descend in packs. In the queue, the mating ritual would begin. They would size each other up and pair off, giggling and bopping to the music. People go crazy for fairground music. Despite this, there was always a gap between partners. Sometimes it was small but it was always there, as if…