It was early spring, nearly like now, before Columbine, and I was drinking again in that bar perpendicular to the office where they’d housed me. I was with a couple of the bankers and J., the gay man who refused to admit what he was. He knew I knew, and that I wasn’t going to judge, that I liked him as he was. So he hovered close like security, almost like a pimp, and he was lovely to drink with and say much of nothing to. I slept over at his, overlooking the river. I took men back there. He did, too. It was a good arrangement. It was all right between us.

Drinking in that bar. And as usual, I’d had a lot. It was a Thursday night, and that was the one night in the week when that dead city came alive even when there was no baseball game at the stadium just across the way to flood them all in. Prospect Street. Go a few blocks down and you’d see the hotel that Led Zeppelin trashed in the ’70’s; you could see the hookers coming out and walking up and down until cars stopped and they got in and went for a ride. Ride, yeah. Ride. Thursdays were a good night for rides, with all the businessmen who stayed downtown to drink in anticipation of the weekend.

One of the bankers said that evening,—Your face isn’t the usual. I’d like to paint you.

—Do you paint, I asked him absentmindedly.

—No, but if I could, I would, he said.

—Ah, I said, and took another swallow.

—I need the toilet, I said to J. —And then you’re driving me home.

—Baby, he said. Stay a little longer. It’s too early.

—Yeah, I said. And I made my way up the staircase to the unisex bathroom.

When I came out into the hall, the last one I’d fucked and ended things with was there. K. He saw me and called me. Not a banker, not one of the work colleagues. He was far out of that circle. I was swaying, I’ll admit. I was well on my way. I’d been there for a while. The music was deafening and he leaned into my ear to tell me what he did.

—Come back, baby, he said. —I miss you. Come have a drink with me.

—No, come on, I said, shrugging him off.

—We’re not finished, he said.

—No, we are, I said. —Leave it. It’s over. Get one of your others.

—You’re here now, though, he said. —There’s no one else here. You come with me now.

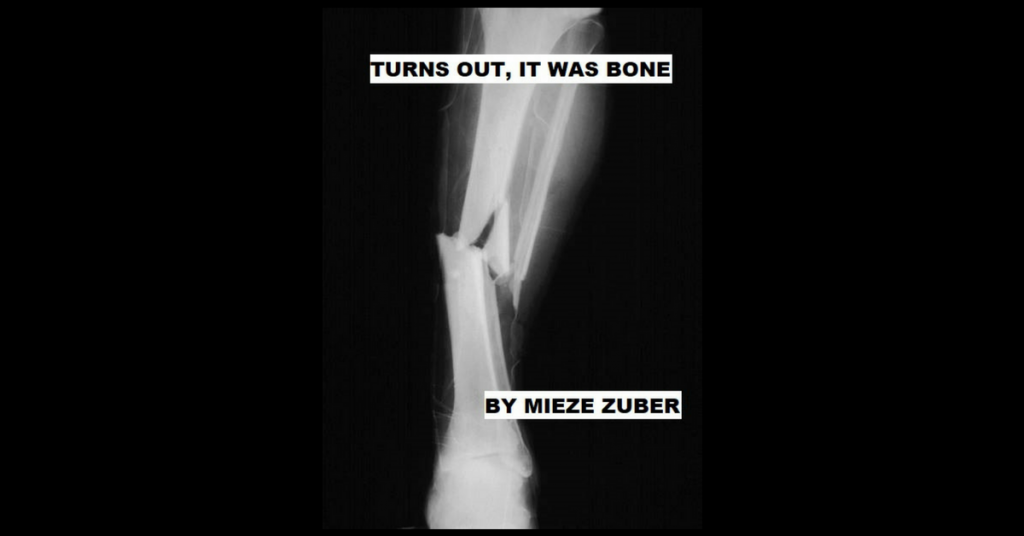

I didn’t say more. I went back down the stairs to the bar. And then he was behind me; I felt him and there were no words coming from him but his fists were out, I felt them on my head and half turned and got one to the face and then I was falling. And I reached the bottom, the ground floor by the bar, and I tried to stand and someone I didn’t know, she was stopping me and saying, —NO, DON’T MOVE. And then I felt more hands on me, holding me back. I tried to stand and they stopped me. I saw white through my black stockings and thought, —What’s that?

Turns out, it was bone.

They phoned an ambulance while I kept saying, —I’m fine, leave me alone, it’s fine. I was transported to the inner-city charity hospital emergency room. Saint V——‘s. Laid there on a slab of an examining table, next to a homeless guy in the next bay. He was crying and I wasn’t. I just ignored the pain running up my leg, into my pelvis. I wanted to smash something. He was crying; he was crying for his mother. I looked over at him in a haze of something and saw his weathered face, his black ashy skin.

—You’ll be okay, man, I said. My voice didn’t sound like my own. It was high and thin and cracked. I sensed some kind of feeling, some deep and sharp thing. I still couldn’t identify it as pain.

—I’m going to die, he said. Wailed it.

—No, no. You’re fine. You’re going to be fine.

—I’m BLEEDING, he screamed. EVERYTHING’S BLEEDING.

—Shh, I said. Shh. It’s all OK.

—I’m telling you, bitch, I’m FUCKIN’ BLEEDIN’. I’M DYIN’.

I didn’t say more. The pain had manifested; the pain was making itself known. And I was unable to even turn on my side to see if he actually was bleeding. And there I was lying there on that fucking slab of an examining table, and I just wanted to get up and walk away and I couldn’t. I lay there, trying to erase K.’s face from my head. I closed my eyes and gritted my teeth.

+++++++

I’d chosen K. because he was precisely such a brute. I’d met him in that very same bar in late winter. Another Thursday. J. had crinkled his nose at that choice. K. was blue collar and sweaty, garage car mechanic, shaved head and Neubauten tattoos. He bought me a couple of shots and actually sniffed me.

—Don’t tell me that one’s coming home with you, J. said.

—Why not? I’d laughed, and hugged him.

—He’s disgusting, said J. —And he’s a fucking freak. I don’t need a radar for that. Yours is totally broken. Pick someone else.

But I didn’t. I knew J. was right. I’d seen it myself. I knew K. would fuck me up but good, and it was exactly what I wanted that evening. J. wouldn’t let me stay at his that night. He told me that if this was the new romance, I could take it back to mine. And I accepted that, and I did.

I was bleeding from various places the following morning. I let K. out the door at 5 am with stinging promises of more. He came back twice, and we went out together once, and then the fourth time we got together, he kept talking about other women. And he left his pager on and kept using my phone to answer their calls, arguing with them about this and that. Funny I couldn’t put up with it. It wasn’t like I was in love or anything. I just found it annoying.

When he hung up from the last page saying, —Sorry, I’ll turn it off, I told him that I would rather that he leave. We argued and he gave me a few slaps and punches, and I told him, —OK, enough now. Go home.

Surprisingly, he did, and he left me alone. Up until that night in the bar, early spring. April 8th, I think it was, into the early morning hours of the 9th.

+++++++

After the x-rays, they told me my tibia was fractured and close to a break. They would keep my leg mobile. J. was allowed in to see me then.

—I phoned your mother, he said. —Your dad picked up.

—Fuck, I said.

—You’re going to need him tomorrow, baby, he said. —How else are you going to get back to the hospital? They’re about to release you right now. I can’t take you.

—They won’t give me anything for the pain, I said. My face was wet, and he wiped it for me.

—I’ll get you something, don’t worry, he said. —We’ll get you home tonight and stay with you.

I didn’t say anything for a few minutes, and he didn’t either. J. If I could explain to you how much I miss him in this exact moment, writing this.

—And don’t worry about that fucking asshole, he said, almost as an afterthought.

—K.? I asked.

—Yeah, K. No one called the police. You’re not going to have to worry about him again. A couple of guys from the bar took him out around back.

+++++++

Nearly two decades removed from all that. It’s sordid, it’s shit. I’ll tell you more about that emergency room. I’ll tell you how that man next to me cried for his mother and asked me to sing him a song to keep him occupied. I’ll tell you how I gave in and did it, in a cracked and off-key voice. I’ll tell you how much it hurt, and how much I deserved it or didn’t and got it anyway, how playing with fire guarantees you’ll get burned and how it echoes, how everything from the past resonates, how your entire life of skull fractures and bruises the school nurse questions leads to it. How it echoes. I’m here, safe now, removed. But all the echoes. It goes on and on until you can finally call it past and can finally call it over. And what it means when you reach back and dredge it up because you realize it’s never over until you really call time on it. Just know, this is calling time on it. The narrative from then isn’t finished, but I’m calling time on it now.