Welcome to X-R-A-Y Specs, a film roundtable in which four of our radiological technicians converse about movies. This edition’s selection is Toys, an unusual Robin Williams vehicle from 1992. Our conversation follows.

Tex Gresham: I’m gonna do something here I haven’t done yet: START THE CONVERSATION. So here it goes. Good luck and I’m sorry.

I want to acknowledge that this movie absolutely falls apart in the third act. The entire showdown—while metaphorically successful in its use of old vs. new toys—fails in relation to the rest of the story. It dips into cliche Hollywood explosive conclusion that doesn’t work with the narrative – though it sets up this conclusion from the very first installment of tension w/r/t the story. But everything before this let’s-take-on-the-big-bad-guy-with-our-own-form-of-violence that feels like an absolutely adherence to the Save the Cat formula, everything before that, to me, is an exploration of a moral theme that resonates with Right Now—the Honest Self (the old toys that take work to make work) versus the Easy Self (the default combative war toys that don’t take any effort to exist).

At the end of the day, this is a weirdass movie that only the early 1990s could’ve created, an adventurous big-budget film of quasi-visionary filmmaking that existed when studios had the balls to give money to outside-the-norm stories. The humor doesn’t always hit the easy notes—or any notes at all. But it almost always hits the lowest common denominator. To me, the whole thing feels as if Pynchon was hired to write a broad family-centered comedy that ended up getting bumped up to PG-13 and never really found an audience. It’s a movie that—like Drop Dead Fred—will always bring a smile to my face and I’m happy to bring it into the conversation here.

All that being said, I have to ask: what the fuck is the sea swine?

Katharine Coldiron: I think it was meant to be a submarine or a U-boat, to go along with the war theme, but an organic one. I suspect a prop department that ran out of time.

I guess I’m having trouble seeing the war toys as representative of an Easy Self. I know we don’t see them being manufactured the same way we see the other toys being made (replete with a quasi-reggae, bleakly minor-key theme sung by Tori Amos, of all people), but the children doing video game testing look like they’re doing work. I’m not saying there’s no binary between war toys and regular toys in this movie—I mean, it’s impossible to miss—but I find it a lazy binary that seems to represent Capitalism = Good vs. Military-Industrial Complex = Bad. As if those two ideas could ever be extricated from each other.

I guess I’m having trouble seeing the war toys as representative of an Easy Self. I know we don’t see them being manufactured the same way we see the other toys being made (replete with a quasi-reggae, bleakly minor-key theme sung by Tori Amos, of all people), but the children doing video game testing look like they’re doing work. I’m not saying there’s no binary between war toys and regular toys in this movie—I mean, it’s impossible to miss—but I find it a lazy binary that seems to represent Capitalism = Good vs. Military-Industrial Complex = Bad. As if those two ideas could ever be extricated from each other.

Now that I say that, I’m not sure the movie even really invokes these ideas as we know them. We never see the regular toys being sold in stores, and we never see the war toys making war in a space outside the factory. The whole movie exists in a liminal space between imagination and action, without real-world money or consequences (even death is just a laugh). The toys aren’t capitalistic so much as they are whimsical, and the military isn’t dangerous so much as it is fetishistic. None of the ideas reach fruition or conclusion—they all float in this surrealistic space.

TG: Right? Like the movie makes no effort to talk about the simple analysis of capitalism vs. military or whatever—even sort of betrays whatever conversation could take place by having the factory make little toy soldiers at the end of the movie. And yeah, it doesn’t show the toys in action outside the factory to give us some kind of real-world context. And that’s because I think the movie isn’t a combative piece about capitalism but rather is a workplace fantasy that operates as a metaphor for the creative process of making a film. As stupid as that may sound.

And when I say “Easy Self,” I’m talking about the apes smashing bones ala 2001 Easy Self—that violence is our easiest and most primitive state. And to be entertained by Alien Al might be a little more difficult than shooting down helicopters—but overall might actually be a little more rewarding.

What I really dig about this movie are the jokes. They’re like a fart in the back of the theater rather than the clown on stage throwing pies at his own face. And most of the jokes are played serious, not really a beat to let them breathe. It’s an odd kind of humor that I think worked for me on a fundamental level—but actually didn’t really work at all.

Rebecca Gransden: This is a truly strange film, and, as Tex mentions, part of that derives from the unlikeliness of it being a product of the mainstream American filmmaking system. Initially I expected some type of US take on the Willy Wonka archetype, and that aspect certainly is there in warped reflection.

You are right, the satire is heavy-handed, so much so that it ends up being of tangential importance, almost as if it’s an afterthought, or perhaps a reflection of what would have been expected of a film of this type, at this time. The relationship of the fantastical factory with its product reminded me of the industrial conveyor belt representation of toy making seen earlier in Santa Claus: The Movie, a more direct critique of capitalism and consumerism. The main targets Toys seems to be taking aim at are the arms industry and the video gamification of warfare, but the execution is so knockabout that any points become vague. It is difficult to pin down the central crux, the raison d’etre. I like the idea that it is a film about filmmaking, and it does have the quality of self-examination about it.

Perhaps the reason it does fall down with its denouement is the confused underpinning you both mention. It simply has no story to resolve, as the narrative foundation and any character motivation is either unclear or nonexistent, so the only option is to fall back on hey, good traditional values toys versus evil military cynicism toys. Fight!

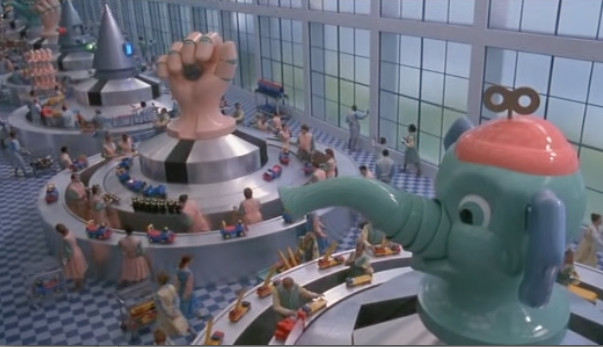

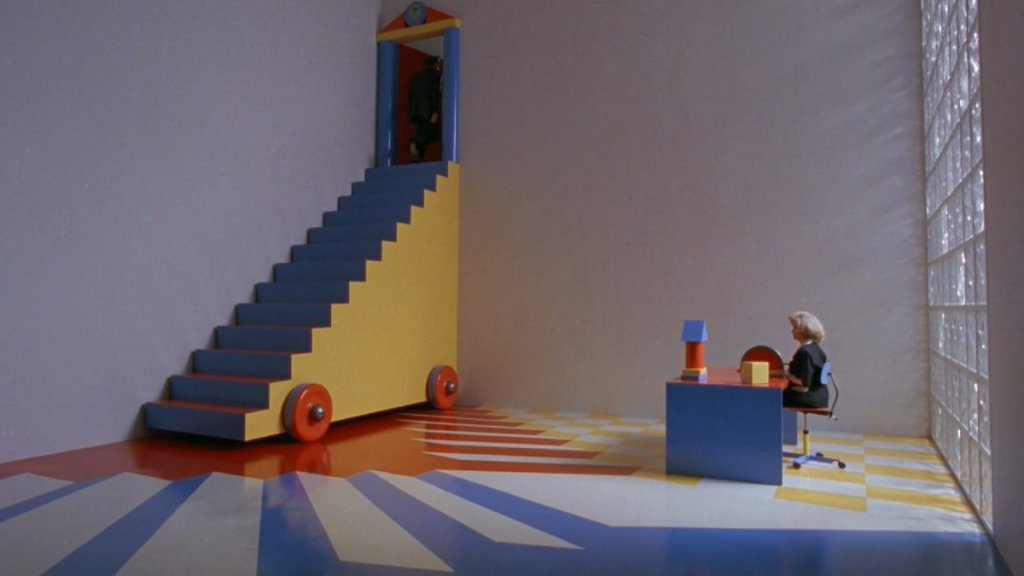

Were any of you struck by how visually ugly the film is? With the obvious influences of Magritte, Pop Art, and surrealism, a film of this budget and vision would suggest something sumptuous, or at least arresting. There is an institutional touch to the primary-colored hues when they are used, and the pastel palette is similarly off-putting, or so I found anyway. The simple blocky style applied to everything seems to reflect the type of design choices lazy planners make for areas intended to appeal to children, but is also reminiscent of the layout of propaganda images. At one point in the film classic propaganda style murals are shown to decorate the walls of a military area, which is a nice, if on-the-nose, touch. For Toys, everything looks drab, even the most colorful areas and costumes. The scenes of the outside Magritte-like fields do hold a dreamscape quality, but I found even these oppressive.

Were any of you struck by how visually ugly the film is? With the obvious influences of Magritte, Pop Art, and surrealism, a film of this budget and vision would suggest something sumptuous, or at least arresting. There is an institutional touch to the primary-colored hues when they are used, and the pastel palette is similarly off-putting, or so I found anyway. The simple blocky style applied to everything seems to reflect the type of design choices lazy planners make for areas intended to appeal to children, but is also reminiscent of the layout of propaganda images. At one point in the film classic propaganda style murals are shown to decorate the walls of a military area, which is a nice, if on-the-nose, touch. For Toys, everything looks drab, even the most colorful areas and costumes. The scenes of the outside Magritte-like fields do hold a dreamscape quality, but I found even these oppressive.

KC: My opinion about that is that the production designer has an excellent visual sense and the director has none. I’ve never been a fan of Barry Levinson, but I’m annoyed that he tried to be Tim Burton for a minute here, because he didn’t have the skills this movie demanded. I wouldn’t have used the word “ugly” to describe the film itself, more like “closed,” but I do think the daring, whimsical production design was shot by a director with virtually no daring or whimsy in him.

TG: Tim Burton wishes he could be this interesting.

Jillian Luft: Have to agree with Tex here. I adore the aesthetic of the film and my first note was, “Could live in this world. Stellar production design!” So, not sure what that says about me. I think the Zevo Toys locale is the perfect blend of whimsical and unsettling, which is the intended tone of the film—as Katharine touches on.

Perhaps I’m drawing on my initial viewing this film on opening day at age 12. I was in awe of the world unfolding before me. The hills in the hallways, the Elephant mausoleum, the duck bed. And then there’s the soundtrack!

RG: The soundtrack is a real oddity. The film announces itself with its version of a traditional TV special music sequence, where Wendy Melvoin appears as the angel on top of the Christmas tree. This isn’t odd in itself, as Melvoin is known for her film score work, but the very formulaic staging clashes with Melvoin’s edgier image. There’s a tension throughout the film, as if it’s being pulled in different directions throughout. Perhaps the explanation is as simple as the director dipping his toes into an area he’s unversed in. The integration of more left-field artists and influences doesn’t settle easy, and adds a somewhat bewildering, but ultimately curious, aspect. The use of a mock Thomas Dolby video as a distraction plot device is extremely fun.

I’ve always preferred Robin Williams in dramatic roles, and his performance in this is a strange blurring of the lines. I’m not sure if the director let him improvise and riff because he was Comic Genius Robin Williams!, or to accentuate the neediness of the character’s comedy. Maybe both. He is perfect for the role, bringing a desperate quality to what are superficially lighthearted moments.

KC: Robin Williams is a born performer, and at his strongest comedically when he can go off-script, so putting him in a movie that’s so artificial and stagey is an odd choice. It’s why I felt myself stirring and paying attention mostly when he ad-libbed, because those moments connected with me as a human being where the script didn’t.

It interests me that this is one of several movies in Williams’s career in which the visuals were much more memorable than the script or performances. The main one in my mind is What Dreams May Come, but this list probably could include The Adventures of Baron Munchausen and, controversially, Popeye. In fact, my experience watching Popeye is what this film most reminded me of: the feeling of alarm, then dismay, and then the slow death of acceptance.

TG: I agree, Rebecca. I always preferred Williams’s dramatic roles, performances where it’s clear he has some boundaries, some semblance of formality. Don’t get me wrong: Williams is wonderfully funny when he riffs. But if you’re not a director who can corral the man, you end up like Chris Columbus—who has 18+ hours of ad-libbed Mrs. Doubtfire bits. It was clear Levinson was not at all interested in the wildman Williams and instead needed the Williams who can pull a joke at a whisper, not a coke-fueled shout. While I too think Popeye is shockingly banal and confusingly uninteresting, Toys feels like it’s eaten just a little bit more spinach and packs a little bit more of a punch.

And the soundtrack is as goofy as the movie—maybe to a fault. If you listen to the DUNE Sketchbook album, the song “House Atreides” has mild callbacks to music from Toys. Hans Zimmer went all out with the Toys soundtrack and it remains, to me, a high-water mark of his career.

And the soundtrack is as goofy as the movie—maybe to a fault. If you listen to the DUNE Sketchbook album, the song “House Atreides” has mild callbacks to music from Toys. Hans Zimmer went all out with the Toys soundtrack and it remains, to me, a high-water mark of his career.

So this movie was supposed to be Barry Levinson’s directorial debut, but instead he made Diner. Had this movie come out in the early 80s, I believe it would have had a better, more lasting impression in the annals of film. Because it would’ve been a strong counterattack to the encroaching Reaganism and its influence on Hollywood—and the oncoming corporate-driven blockbusters. Instead, having been released in the early 90s, we’re left with something that operates as an island, something unable to connect to a time and place.

Toys is available on streaming with a subscription to Starz.