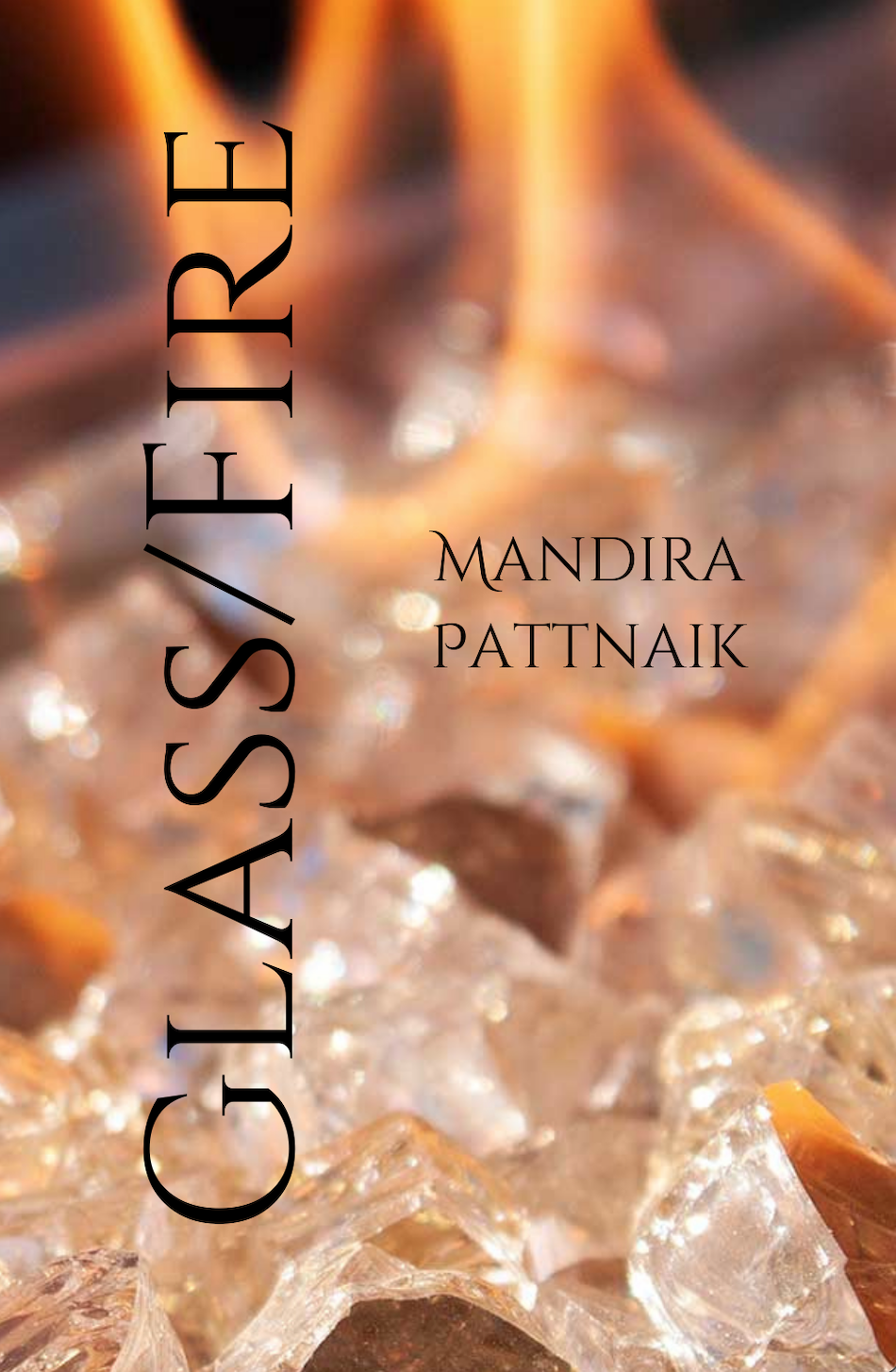

Shifting states. The novel-in-flash Glass/Fire (Querencia Press, 2024) exhibits the unfolding travails of girlhood, a reality adorned in rich contradiction and symbolism. Mandira Pattnaik’s sumptuous language carries forth a deep and sensuous meditation on life’s volatility. The wildness of nature’s forces at their most capricious lend an elemental intensity to fate. A dynamic and revealing exploration of growth, I talked to the author about the book.

Rebecca Gransden: In the mood we were in, fire could be liquid, could be sand, or molten like lava, or flames, licking the last of us.

Rebecca Gransden: In the mood we were in, fire could be liquid, could be sand, or molten like lava, or flames, licking the last of us.

You open the book with the above line. How important are opening lines to you and what does this particular line suggest about the book in its entirety?

Mandira Pattnaik: Thank you, Rebecca. I do not particularly stress over opening lines, though I greatly acknowledge their importance, especially in flash fiction. It’s helpful to think of the opening as the answer to the question: What does it all boil down to? So, it is essentially the essence of what I want to convey. I want readers to feel surprised, or jolted, or pleased, or offended—I want them to respond in whatever way. With fiction, I shepherd some of the things that I know as truths ignoring from which field of study they originate and insert them into my make-believe world. I’ve now grown to enjoy this kind of braiding. This line, while it braids certain facts about the nature of fire, also tells something about ‘us’. Do ‘we’, as much as we are ‘in the mood’, as yielding as glass yields to fire? I asked myself this question that hadn’t been answered or addressed in my mind and wished to take the narrative forward from there. That’s the way I approach writing—a kind of collaboration between knowing and unknowing. It becomes interesting how a fractured pattern forms that I must uncover in the process while exploring what remains unsaid. Since I had the scope of a novella, and it was the first time I was attempting something of this length, I had the liberty to take or not take the chance to provide answers, and hoping the reader will decide for themselves.

RG: How did you decide upon the title—Glass/Fire—for the book?

MP: Glass and fire are unrelated in ordinary usage, and it is easy to forget that something as common as glass is formed by subjecting moldable liquid to fire. But then, glass is fragile. Again, some of the toughest glass-made objects are very useful. Fire is energy, enormously potent, but it is shapeless. It has many forms just like glass. Firepower, however, again like glass, has been tamed to suit human needs. So, all these facts seemed very related, though not in a general comprehensible sense. When I set upon the idea of the novella, the opening story was already out in the world, titled as “Glass/Fire”. After that first piece was published, I was sure it was a title that was full of possibilities and that could be open to interpretation (which I kind of love about titles!), and I had to name the novella that I was writing with the same title.

RG: A recurring theme is that of impermanence, the fluid nature of states, whether that be of the physical, tangible and chemical type, or the psychological or spiritual. What is your approach to transience?

MP: In Indian Hindu religion and mythology, from a very young age, we’re rather familiar with thought-schools such as the cyclical nature of births and rebirths, the virtue of detachment (to possessions as well as relationships) as opposed to being attached, and how change and impermanence is in-built in the universe (as opposed to absoluteness). I understand the doctrine of impermanence is very important to us as a people. Neither are rulers forever, nor is the mortal body to last eternally. Similarly for wealth or happiness, as is bad times and sadness. In Buddhism too, which originated in India, ‘anicca’ is the same doctrine of impermanence, evanescence, transience. Just as life changes in empirically observable states of childhood, youth and death, so do mental events as they come into being and get dissolved. Friends and foes appear and fuse into the mind’s horizon when their job is done. I find this deeply profound. I realize that the recognition of impermanence alleviates the stress of modern living. I seem to course around the theme of transience quite often in my prose and poetry and somehow that has touched a chord with my readers. Simultaneously, I am a great believer of fluidity and interchangeability. These preferences, I understand, gain ground in my writing in a natural manner.

RG: Your language is rich, sensual, often concentrated in its descriptions. You make extensive and poetic use of simile and layered meaning. How much of the style you’ve chosen for Glass/Fire is a conscious decision?

MP: Thank you so much for saying so. I’m grateful for all the praise that my use of language gathers, given that I am not a native English speaker. Also, I am not a trained writer in any sense—no degrees or writing workshops, and nothing to do with writing in my family, so it amuses me when Granta, denying me a bursary that I had applied for, compares my sample piece’s style to that of Gabriel Garcia Marquez. It also propels me to search for what is my true calling, but then I realize that, having had no training is a blessing as I have all the liberty in the world to use my natural style the way I wish to. I have often been appreciated as a lyrical and sensual writer, which of course, is gratefully received. As often happens, one is not prepared to hear anything about one’s writing—I feel so inadequate as an outsider, untrained, writer from the global south. And then one does get more comfortable. It kind of grows on you, and one starts believing in one’s writing—which I guess happened to me. It was never conscious. I am happy I am allowed my lyrical style, without the imposed regulations that academia might have suggested, or which formal training might have eroded.

MP: Thank you so much for saying so. I’m grateful for all the praise that my use of language gathers, given that I am not a native English speaker. Also, I am not a trained writer in any sense—no degrees or writing workshops, and nothing to do with writing in my family, so it amuses me when Granta, denying me a bursary that I had applied for, compares my sample piece’s style to that of Gabriel Garcia Marquez. It also propels me to search for what is my true calling, but then I realize that, having had no training is a blessing as I have all the liberty in the world to use my natural style the way I wish to. I have often been appreciated as a lyrical and sensual writer, which of course, is gratefully received. As often happens, one is not prepared to hear anything about one’s writing—I feel so inadequate as an outsider, untrained, writer from the global south. And then one does get more comfortable. It kind of grows on you, and one starts believing in one’s writing—which I guess happened to me. It was never conscious. I am happy I am allowed my lyrical style, without the imposed regulations that academia might have suggested, or which formal training might have eroded.

RG: Let’s imagine pure mechanics. Not fire. Instead of glass, let’s talk attraction and repulsion. What is to be stirred with two scoops of isinglass so courses of molecules change, or solidify like glue, or say, become viscous?

It’s tempting to see a tension between the scientific and materialist language used in the book and the lyrical and artful, but the impulse to adhere to distinct categorizations on those terms is made moot early on. While you talk of the chemistry that makes us, the stuff of life, the novella interweaves aspects more broadly to present a holistic view. How do you view the scientific when it comes to Glass/Fire? Do you have a personal interest in the sciences?

MP: It’s really difficult to place science and art in two watertight compartments, isn’t it? There’s a constant osmosis taking place, and even one feeding on the other to enrich and enhance each other. I like this interplay. I tend to incorporate this tension between science and art amply in my writing. When it comes to Glass/Fire, the very basis of the work, starting at its title, is heavily drawn from various branches of science. I like to think of myself as a scientific and rational individual who also recognizes the limitations of science, both theoretically and practically. I have a background in science, yes, but I also graduated in economics and worked in accounts and audit—so these are all related and interwoven into my writing now. I’m also a big advocate of science explained and used in everyday life, as should the arts be. Instead of classrooms and seminars, science and arts should be part of life for the masses, not just the elite few.

RG: But being suspicious in a relationship cemented with trust, is really cruel, it eats away the insides like termites.

The novella addresses heavy themes such as adultery, marital breakdown and family strife. Your characters face the undermining of their foundations. How did you go about incorporating these aspects within Glass/Fire?

MP: In opting for exploring certain issues, or the choices of themes we make as writers, I am not much interested in topics that essentially affect an individual or family, such as the themes above. I’d rather explore issues that affect society more broadly, such as hunger, civil unrest or apartheid. Having said that, themes of a domestic nature are no lesser in my mind, just a matter of what I am keener on examining as a writer. To me, issues of adultery or marital breakdown are simply manifestations of other problems in families and societies, and as you very importantly point out, in surviving these, the characters in Glass/Fire face the undermining of the very foundations on which their existence depends. These are ways in which the characters are forced to reevaluate the very basis of their being—and they undoubtedly fight back. I wanted to address how fragile existence sometimes becomes, when the truths and relationships you hold dear to yourself are shaken. I believe this kind of tangential approach to characterization requires more involvement and engagement. Instead of examining the said intensely domestic themes directly, or thinking about these issues as specific to one group or category, I asked myself if I could get to the core of their sadness or unfulfillment, and if there were several minor issues that were responsible for the situations the characters found themselves in.

RG: There was a man dwelt by a churchyard. His wife was the enormous yew tree that shielded him from all. His children came by as autumn leaves, or as some say, they were the cattle that died grazing upon the yew. Sometimes the man coughed so hard, he’d want to be taken out to sea. But they’d trick him—his wife and his cattle-children—saying, the season’s changed and Christmas is here, when nothing ever changed at all.

When it comes to narrative, the novella constantly highlights the meaning to be found in the everyday, that symbolic significance not only exists in a wider cultural manner but is amplified and changed by the personal stories we tell ourselves and are reinforced by family rituals. What was your approach to narrative for Glass/Fire?

MP: I find the symbolism in ordinariness haunting me everywhere. It is like there are things on display, in nature and in people, waiting to be observed and newness discovered, until one realizes that it is only the form that has changed, and nothing ever changes permanently. I think I am going back to the theme of impermanence I discussed earlier. There is a lot of anguish, sense of betrayal, and a sense of forced mental captivity in Glass/Fire, and the only way out of it, at least momentarily, was to search for symbolic outlets for that feeling. I think the undercurrent of anguish is somewhat redeemed through the pursuit of, what I term as, ‘extraordinary ordinariness’. I’m attracted to natural, accessible objects’ magnetic qualities, things and sights easily missed by the unobservant, which are significant in the way they enhance the beauty of the everyday and what is considered the regular or mundane. In that reference, my approach in Glass/Fire was to find that ray of hope in ordinariness as a signifier of extraordinariness.

RG: How does the concept of freedom impact the book?

MP: Ah, now that’s somewhat muddy territory for me—I mean, this concept of freedom. What is even freedom—how free are we? What is the freedom of mind? Is being free in the body enough? There are so many questions, and I can hardly begin to comprehend even if I knew the answers. But yes, I am very much an independent thinking individual and the concept of being free, or at least, feeling free is very important to me as a writer. I routinely turn down offers to write according to a certain theme or plan I’m not enthusiastic about. I respect others’ freedom, and in that context, I think it is very essential that we can be tolerant towards the ‘other’, whatever that may encompass. In this book, the narrator, Lily, their mother, Jo, and Heena—they are all seeking some degree of freedom. Some manage to achieve that ‘limited’ freedom they had been dreaming of, others don’t. So that again becomes slippery territory and I’ll leave readers to decide for themselves.

RG: Gaze at the archipelago around, like it were the pores of a humungous indigo skin. Pass the tiny island where the market still spills with cheap wares people buy. Not you fancying something anymore, though—glass bangles and silk scarves and colored beads mean nothing today. Ceased to have any merit long ago.

At a point in the novella you address the psychological consequences and emotionally disruptive impact of a devastating event. What struck me as particularly perceptive was the observation that in the aftermath of such an event meaning is drained from the world, rearranged or lost. Do you have a philosophical approach to meaning that is expressed in Glass/Fire?

MP: I am not sure I am consciously incorporating the ‘meaninglessness’ of certain things in the aftermath of a particularly traumatic or psychologically draining event, but I think it follows as a universal truth of the human condition. When a relationship is thriving, there are several associated memories, and the lovers hold on to those as proxies of the ‘feeling of being in love’. But when there’s a disruption, the equations change, and the same things have no significance.

The stories I’m interested in and truly invested in, and want to produce, are about finding the truer meaning underneath our superficial lives and delving into the raw, untouched material underneath. That is where the root is—the origin and consequence. After Where We Set Our Easel, my debut novella, I found myself thinking, What is the consequence? In my debut, I was particularly favorable to seeking a hopeful resolution. But in this one, because of its length which allowed me more space, I wanted to approach the questions of origin and consequence with more elaboration, and not necessarily a peaceful resolution.

RG: Looking back, but with an eye on the future, how do you feel about Glass/Fire now? What is next for you?

MP: I feel content with how Glass/Fire has been received by readers. I can perceive that it has generated critical interest and is being seen as a book that stands out from the crowd. This is extremely encouraging because I write about characters and settings that are not very common—especially because they belong to South Asia and the novella almost entirely happens in a coastal region of India. I am also happy that this means I can continue to be as original and faithful to my style as I want to. Following this, I have a collection of short stories that I hope will find publication soon. I am also excited about my debut novel that I am currently working on.