PLUCKERS by Amanda Anderson

I was in the bathroom that fateful day, my butt cheek hoisted up in one hand, tweezers zeroing in on the mole with the other, when my boyfriend walked in. His eyebrows pinched together in disapproval. He asked me what I was doing. I stuttered, searching for a more attractive explanation, then finally told him I was plucking the hair out of the mole on my ass. He asked cheerfully if he could step in and take over. I handed him the tweezers, glad he wasn’t repulsed, only to see a sizable boner emerge in his pants.

And so a monthly trend was born. But it wasn’t that many months before the sizable boner went floppy noodle and the boyfriend began bemoaning the boredom of his life and our relationship. He suggested we were lacking another dimension. Life was short, he said. People are dead. Who? I asked. People, he said. We couldn’t spend what little time we had like this. Like this? Like just waking up and doing shit and going to bed. Being under the impression that this man was my last chance for love, I agreed with a sultry, ok.

This agreement resulted in a number of surprises. First, the new dimension was not a woman, but a man. Second, that man was there for a hair-plucking session. Obviously I was hesitant. I’d been plucking that thing alone in bathrooms for years because it was disgusting. To now find it a point of sexual interest was more than a little disconcerting. But to be embarrassed is not particularly sexy, so I smiled coyly and bent over the edge of the bed.

Eventually, the plucker changed and changed and changed again, and we began to charge a fee. I was accustomed to it by this time, and able to reduce my other job hours. It was a specialized fetish, the sort of thing for which you can charge a lot of money. A rather large waiting list formed. So long in fact, that after a time, the pluckers were asked to submit applications. We received up to 200 applications a month which included age, first name, occupation, hobbies (my boyfriend’s request). Referrals were preferred. So, once a month a lucky candidate was allowed to pluck the single dark hair out of the mole on my ass.

Then my boyfriend took off with a cowboy from Vermont whose hobbies included drinking milk and bringing joy to those around him. He did not provide any references. I didn’t think there were cowboys in Vermont. Which is why I thought we chose him—wasn’t this man funny and interesting, saying he brought joy, drank milk and was a cowboy from Vermont. But it was true. He was a cowboy, and he lived in Vermont. I also didn’t know that this was what my boyfriend had been looking for all his life.

Now I was left alone with my only means of support being a stranger entering my home under potentially dangerous circumstances. But I didn’t care. I was hopeless. In despair. The kind of despair that happens when the boyfriend you thought was your last chance for love and life is gone. So the first choice I made alone was the most dangerous I could muster: a doctor. Anyone who claimed to be a doctor was not a doctor, but someone who daydreams of death and dying, of perfecting a particular kind of violence.

The doctor arrived in a white lab coat with a black bag, the kind of bag doctors carried when they came to the sick at their homes. Had my boyfriend been there, he would have requested the doctor leave the bag outside. The doctor was rather handsome. Which had historically been a bad sign. Handsome men, it seems, believe their handsomeness puts an acceptable shine on savagery. A voice in my head strongly advised against letting him in. It doesn’t matter how much you hate your life, it said (I heard the low chime of fear which warmed my head), you don’t want to be sliced up and thrown in a dumpster with your head and hands in a different bag from your legs. But I’d received a postcard that day from the boyfriend. A cartoon skeleton wearing a wide-brimmed sombrero sat at the base of a cactus, his elbow resting on his knee. But It’s A Dry Heat, the arching caption said, ARIZONA. The boyfriend’s handwriting, appearing as crowded cuneiform marks, overran the open space on the back—across and over, up and around, cleaving the edges of the card. The doctor and his bag were welcomed inside with a kind yet sensuous smile.

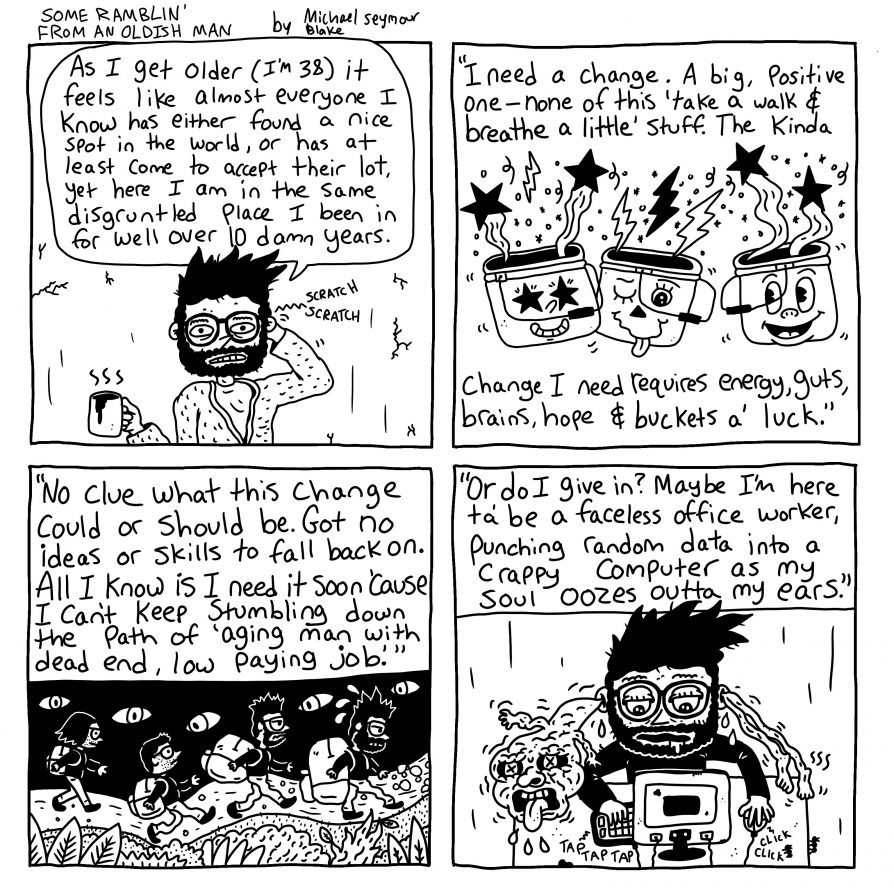

He started in right away. Sighed as he put his bag down, slumped into the living room chair uninvited. He asked for water. Sighed again. I tipped my ass in his direction, asked him in a low voice if he was ready to get started. He took in a seven second breath before telling me things have really been hard for him lately. So many people sick and dying. Men his age are jumping off buildings. Brand new buildings that were meant to be architectural wonders now tainted reminders of mortality. Every day he drove by on his way to work and cursed the man who jumped to his death. Then pitied him. Then cursed him. He finished his water, held up the glass for me to take away and began to cry. Then he pounded his fist on the coffee table. I would understand, he said, once I was his age and your balls and chin start to sag and everyone is jumping off buildings and not inviting you to parties. He let out a low, pitiful noise and put his head in his hands. Then screamed at me to get him a drink. I brought him another glass of water. He looked up at me with a jutted jaw. A drink, he said.

I brought him a whiskey which he gripped like a candle in a church vigil. While he continued whining with his eyes closed I went into the hallway and opened his bag. There were six pairs of socks and a candy bar. I had no idea what this man wanted.

When I got back to where he was sitting he looked at me with bloodshot eyes and asked if I knew what he was saying. I nodded. He shook the empty glass at me, asked me to get him a pair of fresh socks from his bag before asking if I knew what it was like to go through life as a man with overly sweaty feet. I shook my head. He nestled deeper into the chair.

He eventually requested the candy bar and a third pair of socks. After I handed the candy to him he asked if I knew what it was like to go through life as a man who gets faint from low blood sugar. I shook my head. He frowned, then informed me through his teeth that some people think getting tired from low blood sugar isn’t very manly. I told him that sounded very difficult. He nodded and tore into the candy like his life depended on it.

After a few hours, I found the courage to tap on my wrist, apologize, and tell him our time was up. He got up quicker than a drunk man normally would. Melted chocolate ringed his mouth. I stood my ground. He reached into his back pocket. Then pulled out an enormous roll of money, licked his finger and peeled off the bills, licked his finger again for the tip. By far the most money I’d ever made on a visit.

I locked the door behind him and went to the bathroom and threw up. The mole hair turned gray shortly after. Then I bought a scalpel and removed the thing myself.