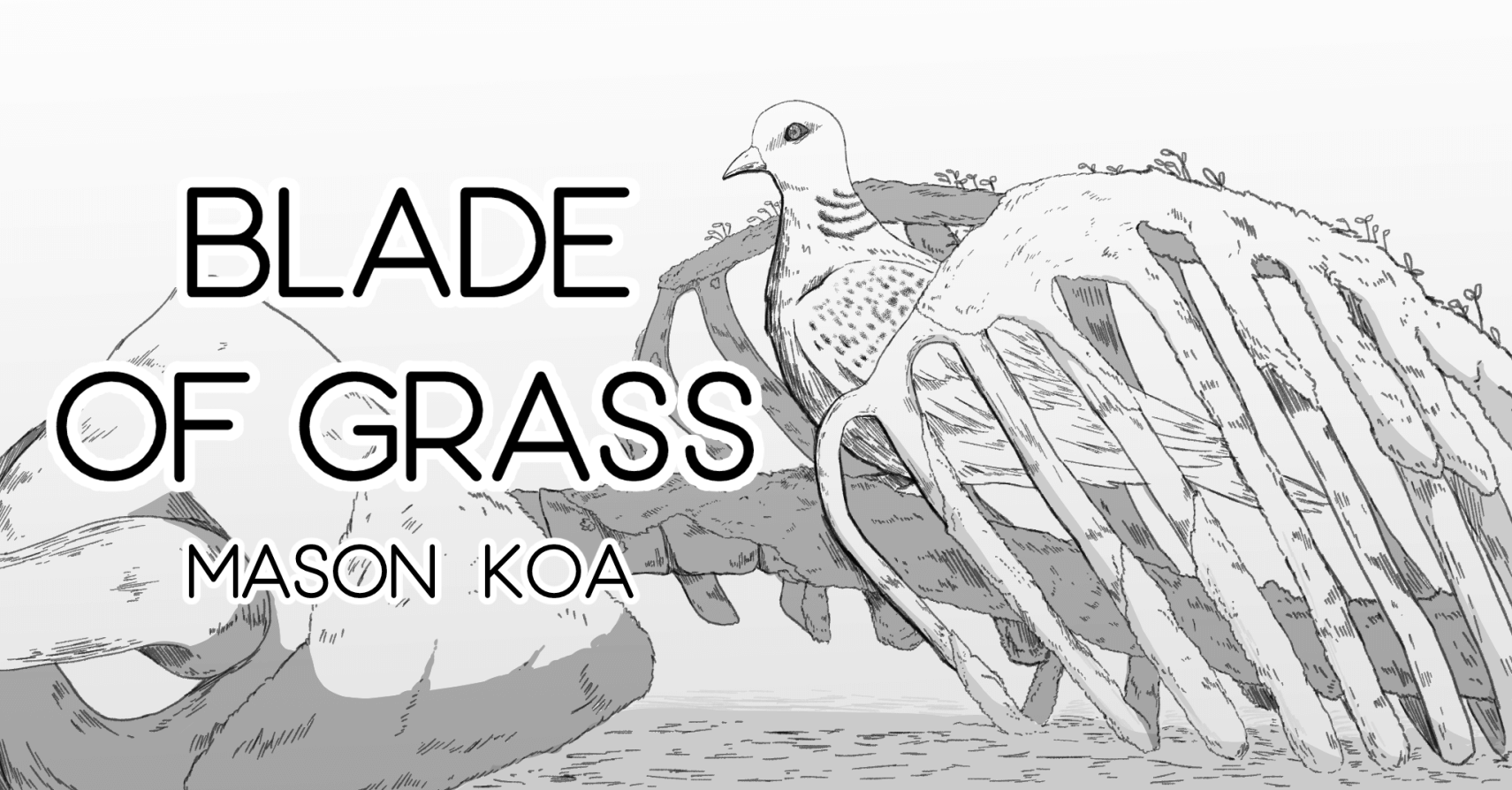

BLADE OF GRASS by Mason Koa

Almost breathlessly, he raved to me that he had done it: He had separated himself from nature once and for all. I pointed out that we ate from nature before a light flickered in his eyes and I cupped my hand over my mouth.