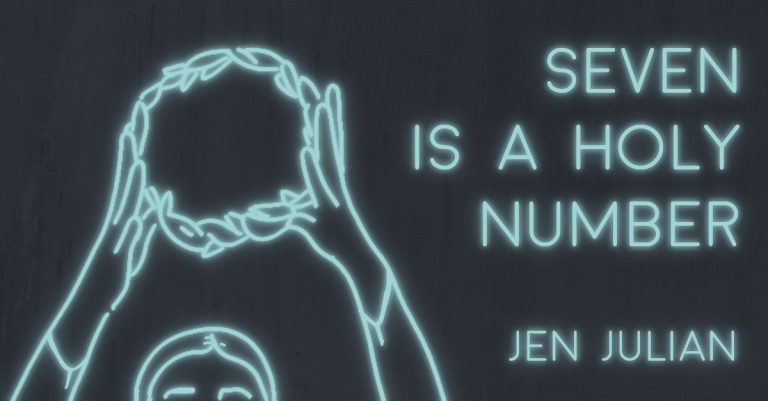

SEVEN IS A HOLY NUMBER by Jen Julian

And yes, that is how many children she has, and I’m talking of course about Mrs. Goth, who every year selects one of her children to be her favorite in a ceremony she performs for us: a blessed clique of friends and neighbors. She lines the children up on the lawn in white folding chairs, and we like to watch their faces brighten with tension, their shoulders rigid, and we like the springy carnal heat of late June, which makes us feel pagan. Mrs. Goth is not intentionally pagan. The truth is, she schedules the ceremony while her husband is away at a yearly business conference. He doesn’t know about any of this.

Supposedly, this ceremony started as a joke, though now Mrs. Goth and the children take it deadly serious. Angelina, the eldest at nineteen, came all the way back from her college in California to participate, even though she hasn’t been favorite in ten years. The current favorite is Jacob, who’s eleven. He took the honor from Margo, thirteen, the previous year, and yes, any observer might think Mrs. Goth is transferring the title in a sequence, from oldest to youngest and back again, or that she’s otherwise appeasing all of her children with a soft and predictable pattern, as Mrs. Goth, who never so much as squeaks a word at community council meetings, gives the impression of being a soft and predictable lady. But this is not the case when it comes to her children. Margo was the favorite four years ago when the honor went to Emma, Jacob’s twin, only to jump back to Margo the following year. We knew from the look of shock on the children’s faces—and the specific look of shameful pleasure on the face of Margo—that Mrs. Goth’s choice was unexpected. We knew intimately the demon grin of Oliver, the second eldest, who was favorite two years in a row before finally seeing the title passed along again to Charlotte, the third eldest, who once snatched it so gleefully from the baby she was scolded by her mother in front of us and went to bed early for the shame. The baby is Wanda. Along with Angelina before her, Wanda hasn’t received the title since.

This year, on this evening, the dayglow wanes and the lightning bugs come out. Mrs. Goth has set up a table of pinwheel sandwiches and expensive cheese, which we peck fretfully, and a crystal bowl of boozy punch, which drowns the lightning bugs and makes our conversation sparkle. The children, still stiff in their lawn chairs, are dressed in church clothes. Their feet root to the ground like dandelions. Their mother is a kind and obsequious hostess, but when she’s making her choice, she tucks her hand behind her back like a decorated general. Yes, in the past, we have put money in a pot, though that’s not the point. We have never tried to persuade Mrs. Goth to choose one child over another. The point is that it’s not anyone’s choice but hers, because we don’t know what elegant criterial chart Mrs. Goth goes by, and we have decided that any one of her children are average enough be the favorite at any time, that they are all equal parts charming and irritating, intelligent and stupid, and they vary almost meaninglessly when it comes to their creativity, sense of humor, athletic prowess, political awareness, and physical grace and style. By now, all have made neighborhood contributions they can be proud of—Jacob’s YouTube videos and Charlotte’s paper craft and Oliver’s volunteer campaign work for the county warden—though Emma’s newspaper-worthy success last year with amateur theater told us that measurable accomplishments are not the deciding factor for Mrs. Goth. Or, maybe, Mrs. Goth thought Emma’s performance in The Gondoliers wasn’t any good, and who are we to argue with that.

The children, if they know their mother’s criteria, have said nothing about it to the other neighborhood children, or maybe they have, and everyone involved is sworn to keep it secret from us grown-ups, the same way we’re sworn to keep the ceremony secret from Mr. Goth. But we wouldn’t want to know the criteria, even if we knew how to find out, because we like to think the favorite is more divined than selected, because we have talked about it over drinks on back porches, around fire pits and masonry ovens, and in the shallows of our swimming pools: this is our I Ching, this is the primal blood-spill of chicken entrails, this is our peek through the door of the celestial house. Neither we nor the children have the power to control this outcome and nothing can prepare us for it, but that is where power is, and here in this neighborhood power spirals its infinite coil into the secret mind of Mrs. Goth.

We watch her children, seated with calm and anxious dignity, sweaty hands folded in their laps. Their toes recoil like worms in their sandals as their mother strides by again. She’s still deciding. We watch and hold our breaths as she bends down and opens the ceremonial bin, brings out the dried laurel crown, silk ribbons dangling. Every year, we smell its delicate bay scent spicing the lawn, hanging over the heads of the children. But which head? Whose perfect head? We lean forward to hear Mrs. Goth’s whispers: Who is it this time? Who is it? We think: How long can we hold this ecstatic breath? We think: how will the universe have realigned when Mr. Goth comes back home?