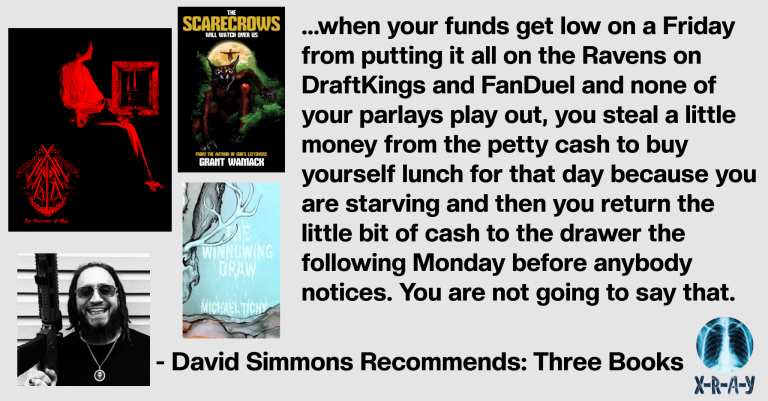

DAVID SIMMONS RECOMMENDS: THREE BOOKS

The Winnowing Draw by Michael Tichy (Castaigne Publishing, 2024) “Keeping a fire alive is an act of vigilance. The darkness merely awaits.” The Winnowing Draw is like Bone Tomahawk meets The Neverending Story, with beautiful language that really immerses you in the time period. We are in 1880 where a poor teenager named Cecil is on the run after accidentally (or not so accidentally?) murdering his best friend, another boy, but from a privileged and prestigious background. Meanwhile, a colonel, his kidnapped two-spirit guide, and his band of ragtag soldiers are on a hunt for American monsters. The wild

NOTHING CAN BE DONE by Pham Thu Trang

The singing starts before dawn. Four or five in the morning, when the alley is still dark and narrow and holding its breath. The houses face each other across a strip of concrete barely wide enough for two motorbikes to pass without touching. Sound has nowhere to go here. It hits walls and comes back. She throws her doors open and sings. She is about twenty, maybe. I know she has a neurological condition—people say it quietly, with the tone that means explanation and permission at the same time. We have spoken before, in small ways—offering snacks, simple questions, asking

ELEPHANT EYES by Kristopher Monroe

When I was in fourth grade my mother disappeared and I never saw her again. At first my father wasn’t sure what to tell me but he realized that the truth was better than obfuscation so he told me she was admitted to a sanitarium which I didn’t understand so then he explained she was simply sick and resting which I definitely did understand. For as long as I could remember my mother was sick in a certain way. She’d be doing dishes or loading laundry or scrubbing the tub and suddenly become overwhelmed with sadness and break down weeping

Things I Hate A Little Bit Less Than Others By Travis Jeppesen (author For Those Who Hate a Little Bit of Everything)

The stories of Diane Williams After finishing a thousand page novel a few years ago (Settlers Landing, ITNA Press, 2023), as a way of “recovery” I started writing these very short stories, many of which are gathered in this latest book. Diane Williams has built an entire career out of writing such miniatures – I hate the term “flash fiction”; one is almost tempted to call them “fragments,” only they’re not. Williams’s stories, along with Kafka’s parables, might look like fragments; in fact, they are wholes. (When we speak of fragmentation as form, we’re really talking about texture.) Equal,

by Mike Topp

$25 | Perfect bound | 72 pages

Paperback | Die-cut matte cover | 7×7″

Mike Topp’s poems defy categorization. That’s why they are beloved by seamstresses, pathologists, blackmailers and art collectors.

–Sparrow