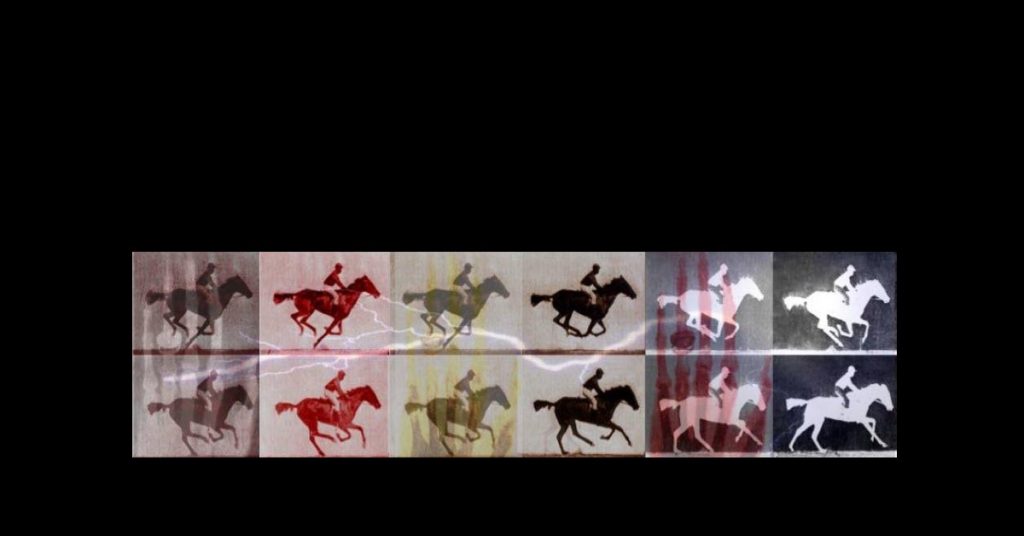

THE HORSES, THE HORSES by John Torrance (Megan Pillow)

All in all, it’s a good place to stop for the night. There’s little work to be done and a beauty of a view: a tranquil lake at the bottom of a grassy hill, lush and electric green beneath the early evening sun. No other cattle to crowd them. After they put up tents, perhaps a bit of play to shake off the day’s ride: a tune on Morton’s banjo. Then grass for the cattle and grub for the men: canned beans, or maybe a rabbit that’s a touch too slow, something that makes the belly full without turning it. They’d learned that lesson with the prairie dogs near Jackson Hole.

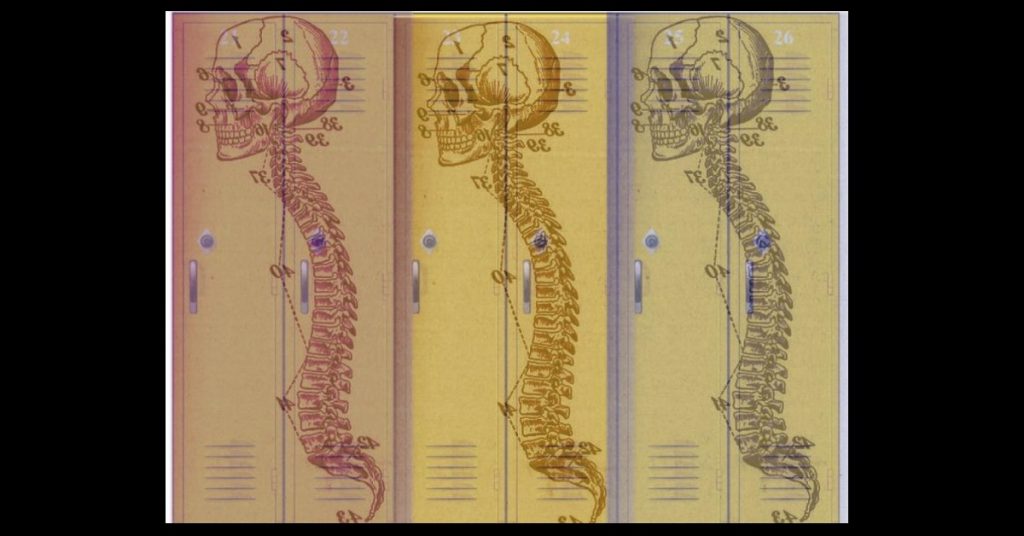

While Amos and Morton unsaddle the horses and shoo the cattle, Jack is staring at something. Amos shakes his head. Still distracted. Watching the animals. Amos watches the grassland, which looks like his palm when he touched it to the barn that time and drew it away, wet and green and dripping great dots of color onto the bleached ground, leaving a half dozen lines trailing dull across the wood like a boy had run his hand there instead of a man. The memory of those fingermarks makes him shiver. They’re still on the side of that barn in Cheyenne, as if the ghost of him is running its fingers along the wall.

By the time all the tents are up, it’s dusk, and the three of them are worked out. No time for music. Clouds are gathering: big, dark, and they bring a chill. No wind. Just a slow, sneaking cold, like an icehouse door left open too long. Amos winds the rope that tethers the (quiet, quiet) horses to the makeshift hitching post till there’s no more play. Morton spoons beans onto tin plates. Amos makes a face but takes one, hands another to Jack. But Jack isn’t paying a lick of attention. His face is drawn, dull. He’s staring at the horses (are they staring back?). Where Jack’s looking, there’s nothing but horses. He’s been restless the past few nights, woken Amos with his whispering. Mornings, he’s always sitting by the dying fire, his eyes bruised, a blanket around him.

What’s wrong? Amos always says.

The horses, says Jack. The horses.

Amos elbows Jack. He takes the plate without taking his eyes off the horses.

Boy’s got a case of the creeps. Just one more night (there’s nothing to be afraid of), we deliver the cattle, and we can all go home.

The cold is all around them before the beans are gone, needling its way inside their clothing so quick that they all turn in. There’s no more light to work by anyway. The roiling clouds have blotted out the moon, the stars. It’s so dark they couldn’t see a pack of wolves hunting them down the hillside. Best to bury under the blankets and sleep till morning. Amos pulls back his tent flap. Jack is standing at the mouth of his own. His eyes are like the gleam of water at the bottom of a well. Likely Jack is getting no sleep at all.

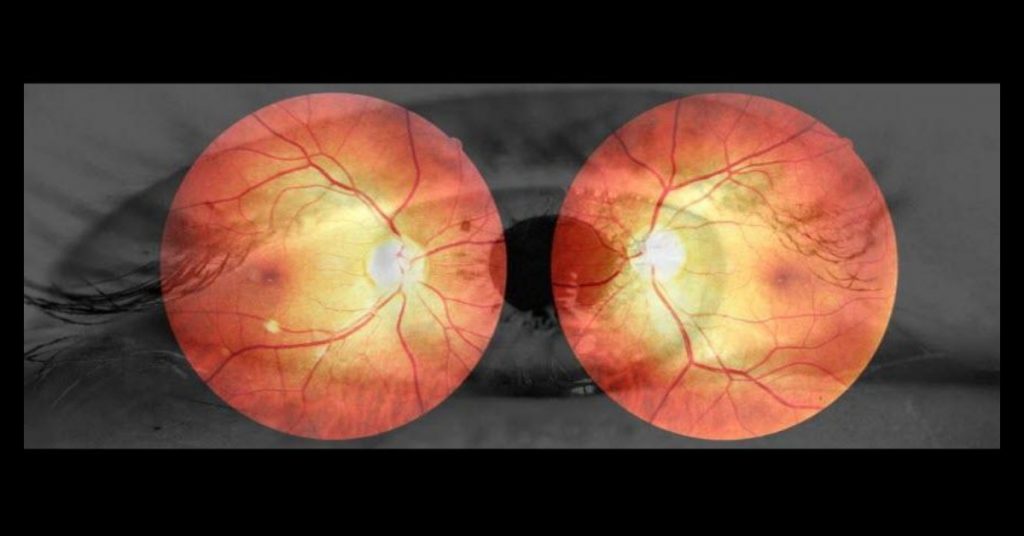

Amos hasn’t been asleep long when a sound wakes him. Quiet, then again: hooves pawing the dirt, playing at something. He clicks his lamp on, lifts the tent flap. The horses are loose from their hitch, standing in a line, their necks close as a clutch of flowers. All of the cattle are gone. He clicks the light off now. He’s tired. His head makes shit up. These are good horses. They won’t (hurt us) disappear. Cattle are probably just over the hillside. He clicks the lamp on again, looks out. Midnight, a horse he’s had since he was a colt, turns his head towards him. His eyes shine like dimes. Out of the dark, Jack is whispering.

The horses. The horses.

I need sleep, thinks Amos. He clicks the light off and hopes for sleep, closes his eyes.

Then, again: hooves. Closer. He clicks the lamp on, lifts the flap. The horses are a few feet away now. Steam rises from their noses like smoke from distant fires. Then the lamp begins to die and he is suddenly terrified. The light flares. Amos can see the rise of Midnight’s chest, the dull constellation of scars spanning his ribs where Amos uses the crop, digs in his spurs.

Good boy, he whispers.

Midnight watches him with gleaming eyes.

Amos’s lamp sputters out. The darkness terrifies him. Anything could be out there. Nothing makes sense in the dark.

The, the sound of hooves again. Closer. Closer.

The horses, whispers Jack. The horses.

Amos presses the switch and the lamp sputters on for a moment and off, and he’s in the dark again all alone, his chest heaving, and light again, then none and he’s struggling, working the switch but the light’s down to nothing again, and he’s desperate no more playing with these fucking animals but the lamp cuts off again and it makes a scream swell in his throat and Jack is whispering again and again the horses the horses again and again maybe this is a dream maybe maybe maybe I am that green-palmed ghost haunting the side of the barn in Cheyenne and maybe I’m still that dull good boy but then the lamp clicks on, and his breath shudders in his throat like a light.

Hooves paw the ground just outside his tent now.

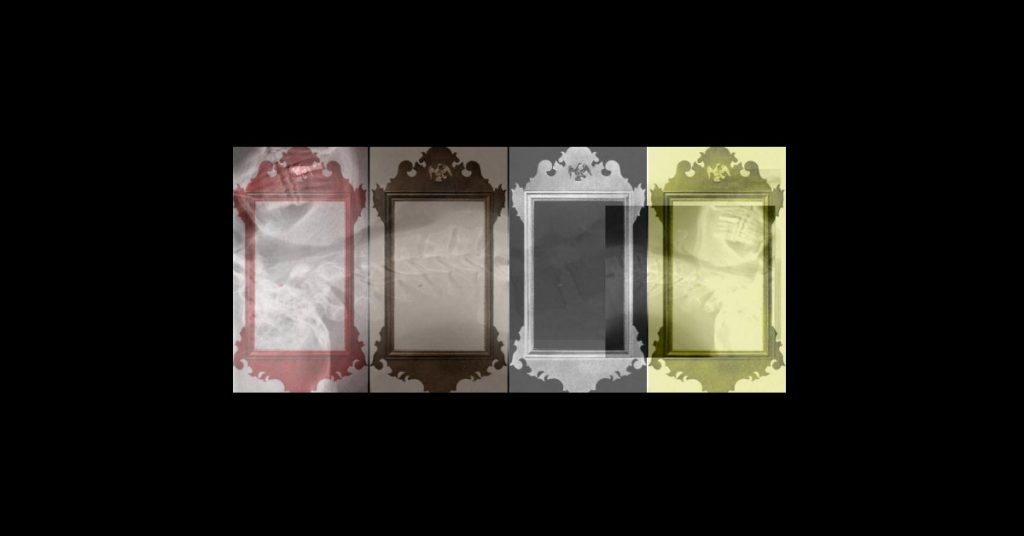

The damp from Midnight’s nostrils wet the flap like breath against a windowpane.

The lamp goes out again.

Amos can hear the click of the bit, like bone, between Midnight’s teeth.

Maybe I’m not here at all I’m not here I’m not but in another field somewhere. Maybe I’m in a parlor yes or at a hotel bar blacking out from drink the dredges of. Maybe I’m walking across the bathroom of room 237 to join a woman in a great green tub. Maybe there’s no escape all this is fake the work is for nothing and no play was a better plan but makes a mistake. Maybe maybe Jack was right maybe maybe I’m stuck in a snowdrift slowly freezing maybe I’m not shining but maybe I’m a dull boy maybe I’m alone in some haunted hotel maybe just writing a novel about this. Maybe -

the lamp clicks on and he sees it then oh God and the horse takes the shape of something, something, something and then oh then it blacks out the sky what is it dear God -

the words were here all along.

Maybe this is the end.

Or maybe

(all my words in the world won’t work to save me and this is the end of time and no nothing will change it you can’t do a thing the play is dead it’s the end I think it makes me terrified of what’s coming but only Jack knows he knows it’s the end times, isn’t it? I am a dull dead boy now)

it is the beginning of something new.

Maybe all all it is work and no play no play and no play the beginning the beginning makes Jack of something of something a dull boy new something new.

Maybe all all it is is work and no play no play and just no play the beginning the beginning makes Jack of something of something a dull boy new something new.

Maybe all all it is is work and no play no play and just no play the beginning the beginning makes Jack of something of something a dull boy new something new.

Maybe

All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.

All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.

All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.

All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.

All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.