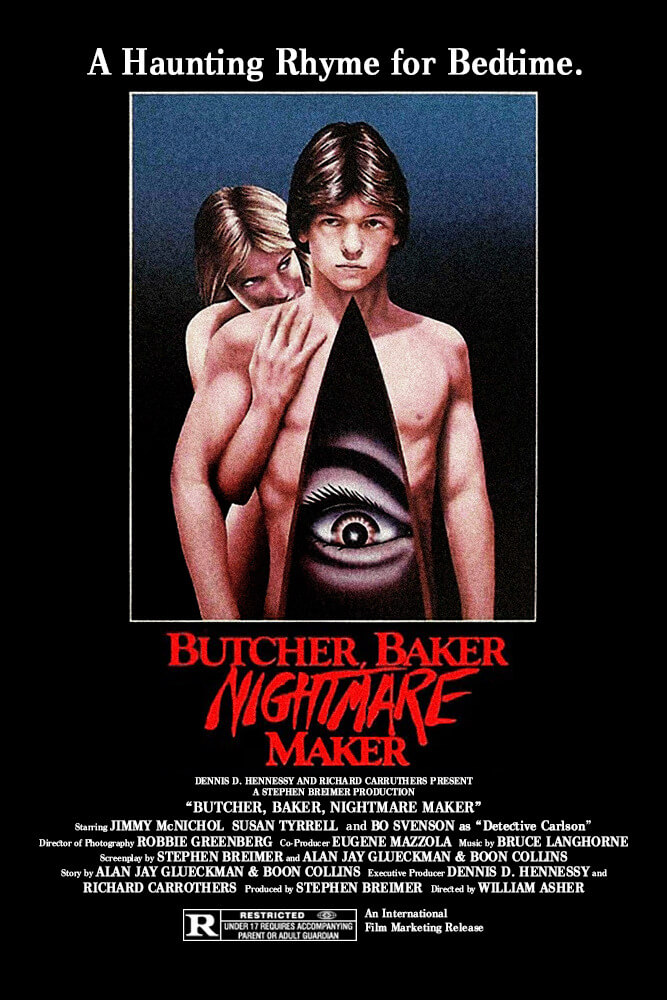

Welcome to X-R-A-Y Specs, a film roundtable in which four of our radiological technicians converse about movies. This edition’s selection is Butcher, Baker, Nightmare Maker, an unusual slasher from 1981. The conversation below should make your Halloween a little Halloweener.

Jillian Luft: I’m stoked I had the opportunity to recommend this batshit gem, knowing that others would then experience its sordid berserkness. I’ve tried to get friends to watch it and I don’t know if the title was a turn-off, but no one’s taken me up on it. Like, where do I even start? I think I have to start with Susan Tyrell’s performance because the success of this film (and I think it’s wildly successful) hinges on the believability of her obsessive love and lunacy. Butcher transcends the 80s slasher category because she brings such an animal tenderness to Cheryl’s psychopathy. She’s at once a wounded animal and a feral beast. It’s a complicated read of womanhood, matriarchy, and domesticity. Tyrell plays it like she’s in a Douglas Sirk melodrama instead of a twisted low-budget exploitation film aping the Freudian aspects of Friday the 13th. I’ve always been a fan of her campy performances but this one takes the cake. See what I did there?

But really why was this movie originally named Butcher, Baker, Nightmare Maker? It’s original and elicits a chuckle or two, but it’s not exactly aligned with the film’s thematic content. Nor is the title used upon its VHS release, Night Warning. Even more vague and puzzling. I’ve given considerable thought to what this movie should be called but nothing is apt. Billy’s Fucked-Up Birthday? Billy’s Psychosexual Senior Year? Billy, Get the Fuck Out of Arizona or Wherever You Live?

Katharine Coldiron: This reminded me of The Mafu Cage, which is not a movie I’d really recommend except that Carol Kane gives a complete tour de force performance. The whole movie turns on it. She plays an unstable girl-woman who’s obsessed with great apes, and she keeps one in a cage in her house until she turns on it and kills it and then gets another one. The cycle has repeated a few times when the movie starts.

Katharine Coldiron: This reminded me of The Mafu Cage, which is not a movie I’d really recommend except that Carol Kane gives a complete tour de force performance. The whole movie turns on it. She plays an unstable girl-woman who’s obsessed with great apes, and she keeps one in a cage in her house until she turns on it and kills it and then gets another one. The cycle has repeated a few times when the movie starts.

It also reminded me of The Baby (1973), which I just saw for the first time recently. A family of women infantilize their son/brother so severely that he’s an adult man who acts like an infant. A therapist comes on the scene, but her motives aren’t clear. The ending of a movie hasn’t dropped my jaw open like it in years. It’s bizarre, and not at all easy to watch.

This one is like a combination of those: tour de force performance that drives the movie, really weird family dynamics. My main question was how Billy was so normal and well-adjusted at the beginning with a clearly unstable single mother situation in his home.

And I don’t think I’ve ever hated a cop as much as Bo Svenson in this movie. A raging villain. I liked that even the other policemen were like, buddy, no, you’re going the wrong way with this. I wish Tyrell had gotten her hands on him instead of the way things came out; she’d’ve given him the death he deserved. (But instead the ending was actually kind of resonant and good?)

Julie was a good final girl, but her survival was pretty supernatural. Didn’t like that.

JL: Well, no wonder I’m such a fan of this movie, because I love both The Mafu Cage and The Baby. I guess “brilliant performance from a complicatedly unhinged women carrying a wackadoo premise” is my fave genre.  And all of these movies are featured in my “bible,” Kier-La Janisse’s brilliant memoir/film criticism hybrid, House of Psychotic Women. She tackles films like this by asking why hysterical women characters behave the way they do. What is the socio-political context? What does it say about gendered relationships and issues? What does it convey about women’s sexuality and agency? And I think these questions are posed throughout Butcher, Baker. We empathize with Cheryl even though she’s the mad murderess, and we detest the lawman.

And all of these movies are featured in my “bible,” Kier-La Janisse’s brilliant memoir/film criticism hybrid, House of Psychotic Women. She tackles films like this by asking why hysterical women characters behave the way they do. What is the socio-political context? What does it say about gendered relationships and issues? What does it convey about women’s sexuality and agency? And I think these questions are posed throughout Butcher, Baker. We empathize with Cheryl even though she’s the mad murderess, and we detest the lawman.

Rebecca Gransden: I’m grateful for the introduction to this special level of insanity, Jillian. Beautifully twisted. I don’t envy the task of any marketing team assigned to this film, as, like you say, it gloriously evades categorization.

The car crash that kicks off proceedings, and assists in initiating how messed up events are going to get, reminded me of the accident sequence from 1981’s The Appointment, where the staging is pitched in an over-the-top, turned-up-to-eleven way, and goes on way longer than it should. By choosing this approach, embracing ridiculousness, the film transcends normal rules and falls into the realms of absurdity and dark comedy. Personally, I’m a fan. It’s a great opening, signposting what the audience is about to be subjected to.

Tyrrell’s performance is extraordinary in this. She manages to incorporate levels of oddness I didn’t know existed. While the character is the archetypal overbearing and suffocating mother figure, she also manages to inject Cheryl with much sadness. She’s a tragic figure, as well as a psycho, a person who possesses mental instability of cartoonish levels, and a neurotic who has lost touch with reality, leaving her utterly pathetic.  I saw small glimpses of Carrie White’s mother in her: the pathological abandonment panic, the impulse to keep Billy close to her and separate from the outside world, and the hints at a religious way of thinking, with Cheryl’s basement space decorated like an altar and the shrine to the man who wronged her in the past.

I saw small glimpses of Carrie White’s mother in her: the pathological abandonment panic, the impulse to keep Billy close to her and separate from the outside world, and the hints at a religious way of thinking, with Cheryl’s basement space decorated like an altar and the shrine to the man who wronged her in the past.

I found the cop repulsive as well, Katharine. What a dick! The actor hit the tone perfectly — that type of small-minded casual bigot who blinkers his way into incompetence. The manner in which he dismisses the investigative efforts of those involved with the case is bleakly amusing. In the end the film frames him as a type of joke I think. Inappropriateness from law enforcement recurs throughout the film, with lewd inquiries into the sex Julie has with Billy, and the other officer appearing out of nowhere late at night to question her. It’s unfathomable, like some parallel universe Police Academy skit.

KC: Nice call with The Appointment, which is underseen. I don’t think any car crash could ever go on longer than the one in that film.

While we’re discussing wildly odd performances in horror movies, I want to remind the world of Aunt Martha (Desiree Gould) in Sleepaway Camp (which is full of treasures anyway, but this one is unequaled). She doesn’t take the reins of the movie the same way Tyrrell does; it’s pretty much this one three-minute scene. But she’s just as memorable, in my view.

The difference is exactly what Rebecca said: there’s a tragedy somewhere in Cheryl, even if it’s one that the film doesn’t pin down. Piper Laurie does a good job with a similar idea in Carrie, giving you a sense that Momma was wounded very badly somewhere along the line to become such a bully, but I feel sorrier for Cheryl. She’s disintegrating in front of our eyes. I wish she was less of a full-blown lunatic in the back end of the movie, as it feels like she’s doing Baby Jane Hudson rather than the strange, hungry, poisoned/poisonous woman she’s been up to then.

Tex Gresham: The beginning of the movie succeeds — in a way I’ve never really seen — in giving us the promise that the whole thing is gonna be a big fuck you to the viewer — and we’re gonna love it. The long car crash, the head decapitation with the log, the prolonged final explosion. It was very and this and this and this which is reflected in basically every scene of the movie. And then watch this. Especially the closer we get to the ending. When the parents drive off in the opening scene and we get that little snake rattle freeze-frame of Cheryl, I feel like it almost would’ve been entirely appropriate had she looked into the camera and winked, freezing on the wink.

This movie did two things to me:

1. It skeeved me the fuck out when Billy stabs Cheryl in the heart and we get death number one. The editing, the over-the-top manic facial contortion, the weirdly erotic writhing, the quick open-mouth kiss, and then the collapse into an oral sex position. It added up to a moment where I found myself making a face like I had just smelled curdled milk. It was wrong — but Cheryl almost seemed thrilled by it. Hence the kiss. She had finally been penetrated by Billy. And then when the second death comes and Billy penetrates her with a bigger object, the result is an incestuous la petite mort. They might not have crossed that barrier sexually, but the death was that barrier being crossed for me and it was gross. (In a good way?)

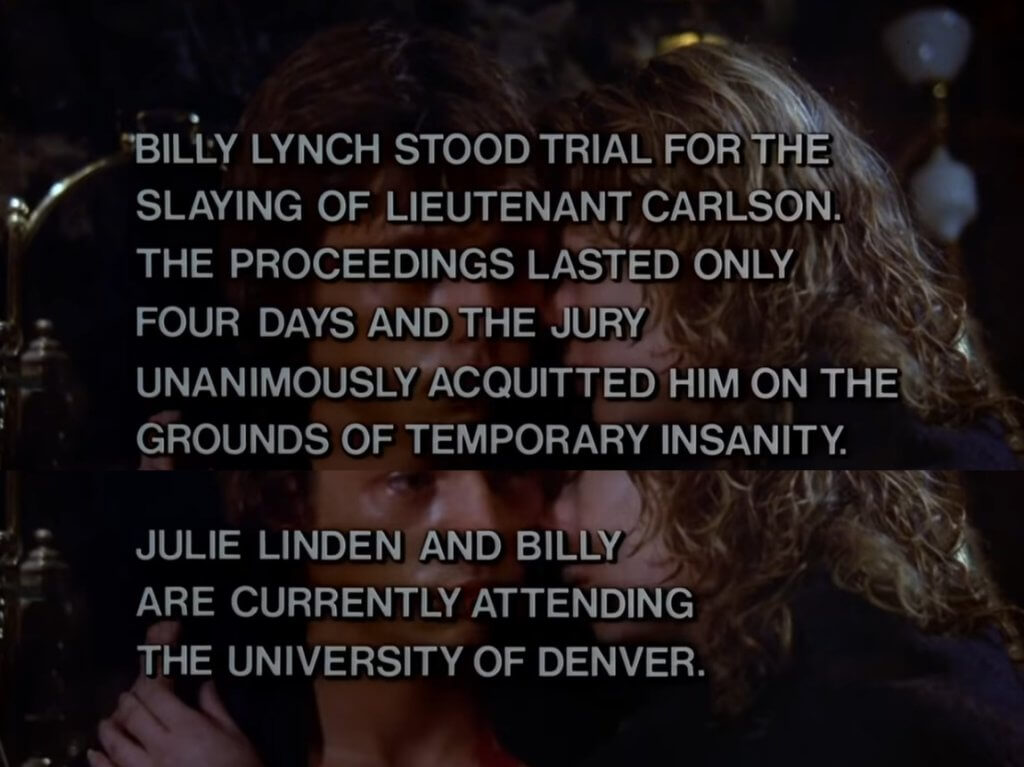

2. I don’t know if I’ve ever laughed as suddenly-loud as I did when this crawled up the screen: “Julie and Billy are currently attending the University of Denver.” I love when movies update us on what happens to the characters after the movie is over. 99 times out of 100 is unnecessary and goofy and laughably great. My favorite is Blood Debts, which became a meme and really doesn’t feel too dissimilar to the one we get in Butcher, Baker. Because I thought, How in the absolute fuck is this guy gonna just go to college? The drive for a sort of cleanly upbeat ending — especially one told in the credits — feels to me like the move of a producer who was afraid that ending as it did visually would be too rough or depressing for the viewer — as if everything they watched since the first scene wasn’t exactly that. And that’s kinda what you want from incest-lite movies — no one’s gonna have a happy ever after. Still, I loved it.

I thought Bo Svenson’s cop was extremely entertaining/convincing/absurd. He’s viciously cruel and repulsive, but is so necessary in the face of the homebound story being told. We need him to get us to fear or be concerned about something other than Cheryl — and in his pursuit cause more problems that lead to more fun and death and perversion. And it’s not lost on me that the man who lets his homophobia fly freely like a $2 bill hanging out of his zipper gets shot by the boy he berated with homophobic slurs — and that the gunshot seems to explode out his ass. It was a moment that felt more rewarding narratively to me than Cheryl’s death. Where one feels depressingly necessary, the other is gleefully unwarranted but deeply satisfying.

RG: The abruptness of the ending followed by the “what happened next” text is hilarious. The editing has some great comic timing in this film. Best use of a balloon burst I’ve seen in a long time.

Billy’s apparent innocence is curious to me. He has a hint of Norman Bates about him, Bates before the homicidal impulses maybe. There’s a wholesomeness and sheltered quality to his demeanor that adds to the general dysfunction of the dynamic between him and Cheryl. From the start, their relationship is overly tactile, uncomfortable from the outside, but Billy is strangely accepting of it. Apart from his efforts to move away from the house he lacks the rebelliousness I’d expect from someone his age, especially given the lack of boundaries Cheryl has with him.

This film is a Freudian’s dream. The way Cheryl constantly offers him milk isn’t exactly subtle, and when this culminates in her forcing milk down his throat before licking it off his neck I cringed as hard as I have about anything I think. The film is great at this, twisting symbols of nurturing, such as mother’s milk, into something wounding and harmful. The scene where Billy wakes to discover himself in the attic room, decorated for him by Cheryl in a style much too young for him, is truly horrifying. But even here Billy seems no more than initially perturbed.

This film is a Freudian’s dream. The way Cheryl constantly offers him milk isn’t exactly subtle, and when this culminates in her forcing milk down his throat before licking it off his neck I cringed as hard as I have about anything I think. The film is great at this, twisting symbols of nurturing, such as mother’s milk, into something wounding and harmful. The scene where Billy wakes to discover himself in the attic room, decorated for him by Cheryl in a style much too young for him, is truly horrifying. But even here Billy seems no more than initially perturbed.

I have to mention the physicality of Tyrrell’s performance. She transforms throughout the film, not only in the very obvious way of when she cuts her hair at one point, but her whole gait changes. As her character becomes more animalistic, her torso seems to morph, and her demeanor changes: she slumps, becomes stocky, juts her jaw, weird grimacing. The way she stomps around, moves within a scene, does a lot to amplify the uncomfortable oddness at the heart of the film.

TG: Rebecca, yes! That was something I actually really admired about the film – her progression into the Id as the Ego fails to fight the urge. By the end of it all, the way she attacks and grabs – and dies – seems less like a person and more like a rabid animal in its death throes. And despite the obvious visual cue, I thought the change of hair worked so effectively to bring us back to the psycho we saw a glimpse of in the opening scene. Her hair is short as she watches the parents drive away, and then it’s longer for most of the film, and then she chops it off again when the murderous psycho comes back full force. Her danger is represented in her hair. It made me think of The Terminator, when Schwarzenegger jumps through the fire and burns off his eyebrows and chars his hair. There’s a clear transition from sci-fi thriller to sci-fi horror at that moment. And Butcher Baker makes the same clear transition – from psychological thriller to horror – with the self-abusive shearing of Tyrell’s hair.

Another thing that’s going to stick with me about this film is that it’s a queer-anxiety narrative that does not, in any way, attempt to sweep that into the subtext. It’s forward, it’s clear. And the movie was put out in a time where I wouldn’t say it was brave to do so, but I will say it’s extremely bold.

KC: Totally agree, and I’m glad you brought that up.

TG: The subtext is also there – as I’m in a camp where I believe Billy is queer to some extent. But it’s the continuous antagonism of the heteronormative villains, and the honest normality of those portrayed as queer, that really flip this movie onto its side and gives me something I could talk or write at length about. The bad guys aren’t just bad because they’re bad – they are bad because they are anti-human. Attempting to bend, through fear and violence, those that oppose to the will of their “normal” view on life – even though their “normalcy” is truly fucked.

JL: Yes! This was primarily why I selected this movie, because I believe it’s super progressive in this way.  Bo Svenson’s cop is so grossly and blatantly homophobic. It’s clear the audience is not supposed to identify with him, but rather perceive his flagrant hate as a flaw. Hence, the law shouldn’t be trusted. The basketball coach’s queerness is presented matter-of-factly. We sympathize with the death of his lover and view him not as a predatory gay man ogling the boys on his team, but as a surrogate father for Billy.

Bo Svenson’s cop is so grossly and blatantly homophobic. It’s clear the audience is not supposed to identify with him, but rather perceive his flagrant hate as a flaw. Hence, the law shouldn’t be trusted. The basketball coach’s queerness is presented matter-of-factly. We sympathize with the death of his lover and view him not as a predatory gay man ogling the boys on his team, but as a surrogate father for Billy.

And yes, I do think Billy is being coded as “queer” but the film doesn’t shape him as monstrous as a result of the psycho-sexual dynamics of his childhood. He’s a victim of Cheryl, sure, but not because she’s turned him homosexual. And Cheryl is also a victim. But they are victims because of the secrets they’ve kept from themselves and each other. Obviously, this is all very Oedipal and that isn’t accidental.

Also, Billy may be one of the first “final boys” presented in the slasher genre. And if we view the film through Carol J. Clover’s premise about “final girls,” perhaps at the film’s (super Freudian) denouement, the director and writer trust that a male audience would identify with the incestual terror and, therefore, Billy isn’t emasculated but rather empowered.

Still, it seems like it ends with him reclaiming a heteronormative identity in the wake of Aunt Cheryl’s death. When that hilarious afterword appears on the screen over Billy and Julie’s traumatized faces, I don’t think most discerning audience members of this genre are relieved. There’s a sense of heteronormative panic – that  the ghost of Cheryl will haunt this relationship. As Tex mentioned, now that Billy crossed the barrier with Cheryl, there’s yet more to unravel. Would have loved a sequel with Cheryl’s ghost filling Billy’s dorm room tub with milk, to be honest.

the ghost of Cheryl will haunt this relationship. As Tex mentioned, now that Billy crossed the barrier with Cheryl, there’s yet more to unravel. Would have loved a sequel with Cheryl’s ghost filling Billy’s dorm room tub with milk, to be honest.

Butcher, Baker, Nightmare Maker is not currently available to stream legally. The Blu-Ray is readily available. A censored version is on YouTube, and you may find a lengthy clip in the Internet Archive should you search for it.