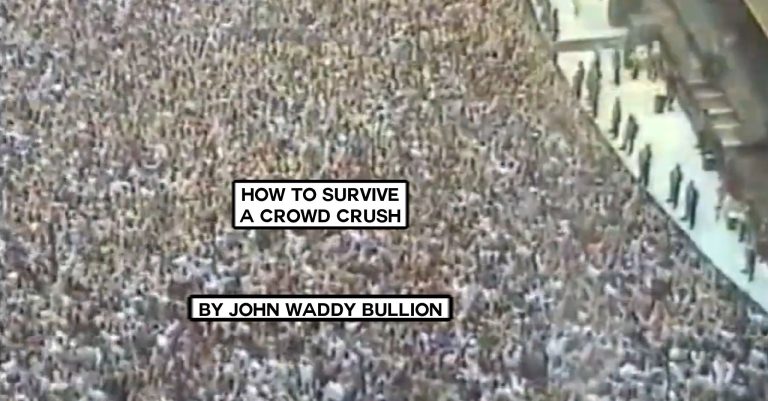

HOW TO SURVIVE A CROWD CRUSH by John Waddy Bullion

First and foremost, don’t panic, baby girl. And please understand that it’s not your fault—you aren’t in this situation because you’re young and dumb, or because your already-questionable decision-making has been dulled by the crumbled-up mushrooms you took in the Porta-Potty out in the parking lot before the show, or because you ditched your girlfriends and joined the stampede to the stage with thousands of others when those first chiming notes rang out; no, sweetheart, the blame lies squarely at the feet of the concert promoters who cared more about selling tickets than about crowd density, and in the hands