Welcome to X-R-A-Y Specs, a film roundtable in which four of our radiological technicians converse about movies. This time, Rebecca has brought us an odd treasure: All-American Murder (1991), a straight-to-video flick that, based on its provenance, should have been a nothingburger, but that we all loved passionately. Our conversation follows.

Rebecca Gransden: Smartest dumb movie or dumbest smart movie. Discuss.

Katharine Coldiron: Smartest dumb movie. This is a smart movie masquerading as a dumb movie. It’s got a ticking clock during most of the middle act instead of the third; it’s got scenes shot as boringly as 1990s television to stage scenarios I’ve never seen in my life; it’s got clichéd lines that lull you into thinking you’re watching something you can zone out to, and then there’s a freaking Sorkin exchange. Seems like a campus murder mystery and then there are three bizarre kills within like an hour. Smartest dumb movie.

RG: It’s wild. Why I’m curious to hear opinions on it, apart from the fact it’s such a blast!

The first time I watched this I nearly switched it off at the start, as it sets up a teen drama, with sickly score and, later, a bouncy 90s tune that could easily soundtrack something like Beverly Hills, 90210. I’m not averse to this but it’s not the area of 90s culture that fits most closely with my tastes. It’s a masterful piece of misdirection. The hard cut to protagonist Artie in bed with Erica announces that this film has a LOT more going on, especially in the way of meta-commentary, but I feel someone else should jump in before I get more into that.

Jillian Luft: This is a whip-smart movie that can still serve as a smooth-brained romp for sloths desperate to escape their lives for 90 minutes (re: me). It’s Blue Velvet meets Red Shoe Diaries (more on that later). And as a rabid fan of both 90210 and Melrose Place, I was charmed by the terrible, treacly pop songs and Josie Bissett (Jane Mancini from Melrose) having a starring role. Also, the dude from the Ferris Bueller TV series? Golden.

The cast alone brought me to my knees in adulation. Richard Kind as a smart-mouthed cop? Yes. Joanna Cassidy playing her character in Don’t Tell Mom the Babysitter’s Dead once she turned bitter and became a vodka-soaked temptress? Dear God, yes. Christopher Walken strutting through crime scenes, all louche and bug-eyed? You’ve sent me an angel.

But the dialogue. The dialogue has to be heard to be believed. Its inconsistency is riveting. At times, so hackneyed it could’ve been written by a crime thriller ChatGPT, and at others, you’d swear Shane Black made some sharp revisions but then got bored. My favorite scene is Walken recounting his divorce and complaining about how his wife left him for a man who owns a cheese factory. I don’t want to quote any dialogue but I want everyone reading this column to watch the smartest dumb movie ever made.

Tex Gresham: Richard Kind playing a tough-guy asshole cop brings this whole movie up to another level for me. But yes, this is absolutely a smart dumb movie – and not even really that dumb. It goes off the rails in a way that only B-side movies from the late 80s/early 90s could. There was an entire market of films like this at that time, the direct-to-video library, that were always films that clearly would have never played in theaters because they were just too off-center to be considered widely. The problem with most of those movies is that, while they have some big cinematic balls, they’re mostly not good at all. Movies made to capitalize on the video market. But it’s obvious All-American Murder was made to be something rather than just some thing.

Had it come out in the 70s, it probably would’ve been one of those huge underground hits that would’ve been given a Criterion release or something like that. But because it was made just post-Reagan and still very much in the throes of the sentimentality/commercialism of Reagan-era cinema, that sort of adventurously weird filmmaking was left to people like Lynch – or it had to be translated into some high-concept genre piece. Made in a different era, it would be a movie more people look at and go Hell yeah rather than a head-scratching Huh? Never heard of it.

And if Jillian won’t quote a line, I will: There used to be good guys and bad guys. Now it’s all just a toilet. We’re sorting turds. There’s no more people. Just bodies. Brilliant.

RG: Whoever was in charge of casting for this does deserve some type of commendation. It’s tough to think of another example where every actor is this perfect for their role. I have to highlight Joanna Cassidy. Erica has relatively restricted screen time but Cassidy injects laudable depth to that character. And Erica gets some of the best lines.

The lines. Jillian mentions the delicious tension between a heightened take on well-worn TV movie cliché and the rampant insanity of 90s irreverence. Walken attacks this script with such oddball glee, it’s a joy to behold. For me, the revelation of the film comes in the form of the lead, Charlie Schlatter, who was not on my radar at all. He plays Artie Logan like a delinquent Marty McFly, with a crazed youthful energy that comes across at once innocent and demented.

Tex picks up on something interesting — the timing of this film’s release. It emerged in ’91, which seems incredibly early in the cycle of “self-aware 90s” this is a part of. How this script came out as a fully formed example of postmodern edge that would dominate for the next few years I’ve no idea. The writer, Barry Sandler, also worked with Ken Russell, which doesn’t surprise me.

Walken too is a godsend for the part of Decker as he has a sage-like quality that lends some dubious credibility to some of the plot contrivances, most notably when he sends Artie off to solve the crime of which Artie is the main suspect. A ridiculous turn but somehow Walken’s cavalier presence allows a sneaking faith that there is method in his madness somewhere.

The manner in which tone is handled is a dream, and the way the film uses TV conventions against themselves to cheekily poke at stereotypes is a joy. Somehow it never takes the leap into snark or clever-clever, managing to remain a hyperreal rush throughout. Many of the kills are pretty graphic for the TV film it initially presents itself as, and that adds a further blackly comic layer, as the contrast between the wholesome setup and the near-giallo body count and gore once again turns attention back onto the film’s self-awareness.

KC: Oh my God, Ken Russell is exactly the vibe. This isn’t much like the content you think of when you think of Russell, but the zany-gritty-violent mix is definitely similar.

I’m not surprised Schlatter never made it, because his voice is suited for Saturday morning cartoons. I kept thinking of how good he’d’ve been as the voice of Howard the Duck. (Not that you could’ve improved that movie a whole lot just by recasting the voice, but the flatness of Chip Zien’s performance is some of the suckitude, and this guy would’ve been better.) He’s great in the part, delivers lines like “Just a stab in the dark” so beautifully, plays the patsy so ideally. I don’t believe very well in his Dark Past, because he seems like a kid who’s in over his head more than a kid on the brink. But he’s likeable and he’s got a smart-only-to-a-point quality that makes him a perfect match for the part.

Similarly, I never quite bought Walken as a police detective. I do not believe he would remain in his job in a normal town’s police department. But the layers of this — that he’s not even really a police detective, in the fabric of the script, so much as a caricature of a police detective (that introductory scene! where he does exactly the thing you’re never supposed to do in a hostage situation [piss off the suspect] in a wildly memorable way! and prevails!), that he’s tapping into persona performance in a part that, in any other movie, would be a character performance, and that both the character and Walken seem to be kind of trying random shit to see what works in this job –- those layers make the whole thing work, and keep me engaged.

Tex, I agree with everything you said about the moment in which this came out, even as I’d argue that this script couldn’t have appeared at any other time. It reminds me of Joe vs. the Volcano, which is exactly the opposite in tone but equally a ride through the unexpected and belongs right in its time period.

JL: Man oh man, you all are tapping into so much here. I’m going to try my best to engage with all of your golden ideas and observations.

I want to linger on Joe vs. the Volcano for just a moment because it deserves our attention. Always. A movie that feels as fresh as when it was released because of its clear respect for the idiosyncratic—those off-kilter details that are charming and indelible and somehow become imbued with meaning they don’t necessarily possess. And All-American Murder shares a similar appreciation for bizarre moments that aren’t at all plot-driven, i.e. the intro scene with Walken that Katharine referred to. This is a movie that demonstrates it’s concerned with narrative by utilizing the tropes of murder mysteries, slashers and erotic thrillers. But it’s also fixated on character, particularly in terms of their quirks and foibles. See Joanna Cassidy’s penchant for vodka. I think she says “vodka” over twenty times in her two, relatively brief, scenes. It’s not at all necessary that we know her preferred spirits to infer she’s a bit of a lush. Yet, it somehow endears us more to her.

And, yes, Schlatter would have killed as the voice of Howard the Duck! I fondly remember his turn as Ferris Bueller in the adapted TV series. It was canceled after a season but I never forgot him in the title role. He embodied the snarky charisma of the original Ferris while bringing his own nervous, manic energy. You don’t quite trust him. He reminded me of Crispin Glover designed for the Tiger Beat crowd, which is interesting considering Rebecca thinks he’s a Marty McFly-type.

Also, concur that the Russell vibe is strong here in terms of that zany dream-like quality he brings to his material. I also saw parallels between this film and Lynch, specifically Blue Velvet. Artie is the delinquent Jeffrey Beaumont inching toward the heart of darkness because of romantic delusions he harbors about a woman and his shady, voyeuristic pursuit of her. Josie Bissett’s character is a less sympathetic Laura Palmer, but she is a willowy blonde with secrets upon secrets. There’s also the fire imagery that echoes both the flame snuffing (“Now it’s dark”) refrain of BV and, obviously, the overt fire symbolism of Fire Walk with Me. This movie is also chock-full of random dialogue and scenes that rival the “Chicken Walk” scene from Blue Velvet, so there’s that commonality.

RG: As this wasn’t my first round with this film I took some time to look at the smaller details, and wandered down some intriguing paths. Firstly, the names given to the main characters. Artie is the arty one. When he first arrives on campus he’s pictured drawing dragons blowing fire at each other and later, in an exchange with Tally, he pleads the case of the arty type to her. Most obviously his artiness is displayed when he presents the vastly oversized canvas to her as a hilarious romantic gesture (that his car is so small had me imagining him pootling over to her place with this massive painting attached to the roof, trying to navigate the streets). Decker asks to be called Deck, which brings to mind a deck of cards, and he is the one to gamble on Artie. I thought I might be reaching a little, but when Deck enters the interrogation scene Artie does say that he has been “grilled by the jokers, you must be the ace.” Tally I’m having more of a struggle pinning down, unless it is a clue to her ultimate role, as she is the one with the body count. This on-the-nose style starts early on, as near the very beginning Artie is shown with his judgmental father, who is literally employed as a judge.

Katharine, I think you are instinctively picking up on my big theory about this film: that Artie is an unreliable narrator and the entire film is his deluded fantasy version of events. Some of the repeated symbolism points this way. At the start we hear that Artie is an arsonist. If we take fire as representing a violent way of cleansing, I think we move towards what is the underlying thrust of this film. Artie’s snake dies in the fire, and the snake, as well as being the traditional snake in the grass, also symbolizes renewal, as it sheds its skin. I think Artie is trying to burn up the person he used to be, and he admits this in a conversation with Deck, when he confesses that he viewed Tally as a way of reinventing himself. Tally also wants to shed her skin, acting out to destroy the wholesome image she finds so suffocating, and at the end she rejects her own face by burning it. I think Artie is the snake. He’s even stamped with the mark of a snake on his arm in the form of a tattoo. If this is so, then it’s not too much of a leap to conclude his replacement snake Cyrano is a representation of the true Artie. I’m assuming Cyrano is named after Cyrano de Bergerac, who, in the play, believes he is too unattractive to be with a beautiful woman and writes letters to her under another guise in order to express his feelings. Artie denies sending letters to Tally, says they have been planted to frame him, but I have my doubts about this.

At the beginning of the film the director frames Artie’s pursuit of Tally as lighthearted, like something out of a John Hughes movie, but taken objectively his behavior is near stalker level. At one point he is literally spying on her from the bushes! This is a great commentary on how Hollywood can perpetuate the idea that the outsider wins with persistence, but there’s a sociopathic undercurrent to Artie’s demeanor that is undeniable. Again, the interrogation scene is key here I think, as Decker picks up on Artie’s charm—superficial charm being a dominant characteristic of the sociopath. Artie responds with a very quick, “It worked.” Artie also confesses to being a master manipulator, and I suspect this is not just referring to his influence on the characters within the film, but on how he appears to the audience.

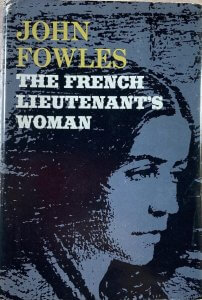

At one point Decker is searching Artie’s apartment and a copy of John Fowles’ The French Lieutenant’s Woman is shown, not just in passing, but in a lingering shot. I assume this is the book Artie previously tried (and failed) to gift to Tally, describing it as a tale of obsessive love. I’ve not read it, and I’d need to look into it closer, but as I understand it the novel incorporates binary/split timeframes that somehow interconnect or have an influence on one another. This further deepens the theme of the film running on different but parallel levels, and of the characters themselves having double lives. Fowles also wrote The Collector, which I have read, and is a prime example of the idea that persistence wins the girl.

At one point Decker is searching Artie’s apartment and a copy of John Fowles’ The French Lieutenant’s Woman is shown, not just in passing, but in a lingering shot. I assume this is the book Artie previously tried (and failed) to gift to Tally, describing it as a tale of obsessive love. I’ve not read it, and I’d need to look into it closer, but as I understand it the novel incorporates binary/split timeframes that somehow interconnect or have an influence on one another. This further deepens the theme of the film running on different but parallel levels, and of the characters themselves having double lives. Fowles also wrote The Collector, which I have read, and is a prime example of the idea that persistence wins the girl.

The film’s logic makes much more sense to me if it is framed as coming from someone trying to retrofit events in their deluded favor. I wonder if Artie even ever left prison, and if he is inside for a crime far worse than arson; if burning up the snake at the start is in fact a symbolic description of a break in his psyche, unable to accept what he’s done, destroying his previous self and creating an imagined world where his acts are justified, explainable.

This could all be over-analysis, but the film does fall into place to me viewed through this lens.

KC: I have to protest about The Collector, because in that book, persistence wins the kidnapped corpse of the girl, not the actual girl. (Which does make it appropriate for this movie? Anyway.) I love Fowles, but The French Lieutenant’s Woman was a popular bestseller and has the reputation for being romantic, and I didn’t read any further into it than that. And Cyrano was the real name of the snake, per the credits. Sorry to be a wet blanket in the face of such glorious over-analysis.

I’ll concede this: the moment of slo-mo burning that indicates Tally’s “death,” and seems like Artie’s dream, did make me think of a Lynchian caesura, where you can choose to believe that what follows is not exactly real. Or only as real as the images passing through the projector.

TG: This dive into Artie’s sociopathology solidified what I was thinking while watching the movie and noticing all the Dutch angles. Almost every other shot is at some kind of slant, skewed in a displeasing way. And I think that’s because it’s emphasizing this delusional nature that Artie lives in constantly. It’s all got this dream-like quality to it, but not a nice dream. And not a nightmare. Which is clearly the space that Artie lives in 24/7 – especially with his fantasy that he could be with Tally. There’s almost a Patrick Bateman-like quality to it all, and each time we’re given that little bit of psychosis, the camera clues us in on it by being tilted.

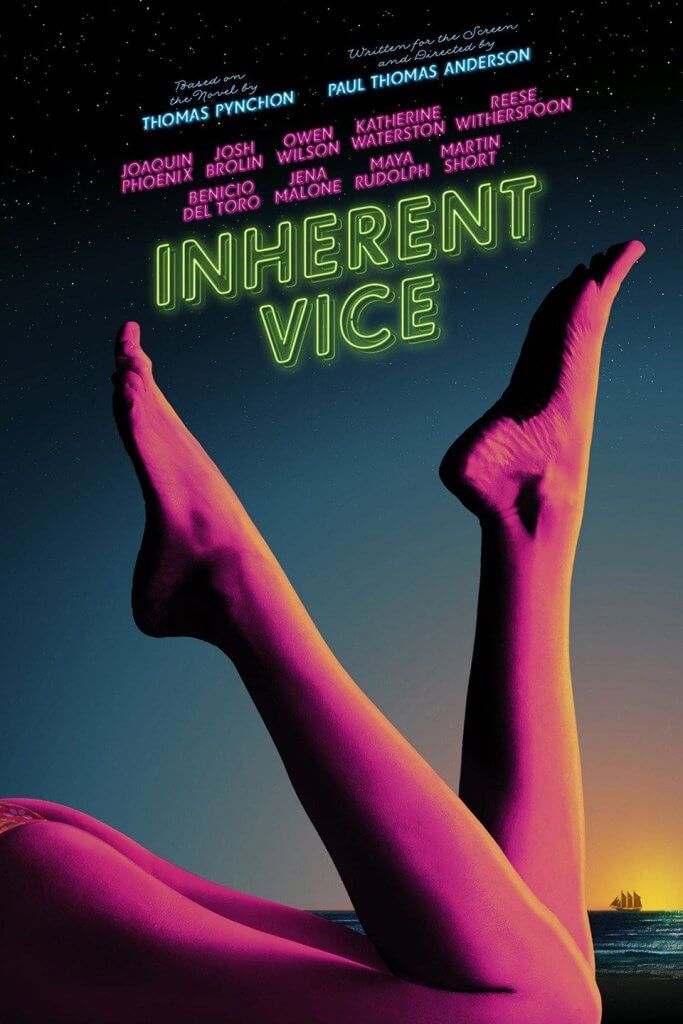

I kinda was reminded of Inherent Vice in that love appears, gives the promise of something, and then forces the main character into a journey they didn’t really want to take. But with Inherent Vice, the female who instigates this journey isn’t really seen again, and only facilitates a collection of moments that leads to the main character doing good deeds for others. In All-American Murder, that journey isn’t at all about love – even though it appears to be. It’s about clearing Artie’s name. He doesn’t want to find the killer to avenge this love that he lost because of a “death.” It’s all about him. And in the end, when we find out who the killer really is, that sociopathology has seeped out of Artie and into the narrative, a punishment for playing with Artie’s life and emotions – if he has any.

I kinda was reminded of Inherent Vice in that love appears, gives the promise of something, and then forces the main character into a journey they didn’t really want to take. But with Inherent Vice, the female who instigates this journey isn’t really seen again, and only facilitates a collection of moments that leads to the main character doing good deeds for others. In All-American Murder, that journey isn’t at all about love – even though it appears to be. It’s about clearing Artie’s name. He doesn’t want to find the killer to avenge this love that he lost because of a “death.” It’s all about him. And in the end, when we find out who the killer really is, that sociopathology has seeped out of Artie and into the narrative, a punishment for playing with Artie’s life and emotions – if he has any.

My ADHD brain wants to jump around so I wanna run back to the weirdness of it all and the movies of this time period – especially the straight to video movies. The first three years of the 90’s was a funky time for films that played the outfield. Studios taking chances on stories that kinda make you go Huh… Okay. Movies that today are seen as cult classics or nostalgia pieces. But to come out of the 80s-driven spectacle and make something like Drop Dead Fred or What About Bob? or Joe Vs. the Volcano, it was clear something was changing, something was different. And I feel like All-American Murder goes even further than any of those previously mentioned films did. It wasn’t just outside the era – it was outside the audience. Outside reality.

I read this quote from Roger Ebert about another early-90s head-scratcher, Clifford. He said, “It’s not bad in any usual way. It’s bad in a new way all its own. There is something extraterrestrial about it, as if it’s based on the sense of humor of an alien race with a completely different relationship to the physical universe.” Dramatic as hell, but after having seen this movie, I get it. All-American Murder isn’t bad, but it’s almost an extraterrestrial product, a movie made for humans by something that has no relationship to the physical universe.

JL: Rebecca, you are blowing my mind with this theory about Artie’s refusal to accept reality or his own dark side. Love this read of the film. Now, I’m seeing Decker as his foil, a man too quick to accept his reality as dismal and doomed while Artie operates under his self-serving delusions. The fire motif totally works as a metaphor for purification and cleansing of the self. It’s what all the characters are seeking to various degrees.

And, yes, Tex, Artie acts under the guise of love but is confronted with the full dismantling of all his romantic illusions by the film’s end. Again, I can’t help but think of  Jeffrey Beaumont in Blue Velvet. He convinces himself that he wants to save Dorothy Vallens and reunite her with her kid but the viewer can see he is, at once, unnerved and intrigued by the sordid underbelly occupied by Frank Booth and his pals. He willingly wanders into the darkness of this world and lets himself be consumed by it. At the film’s denouement, he can longer keep up the charade as innocent savior. Dorothy wanders naked and deranged into his home and refers to him as her “secret lover,” much to the devastation of his high school sweetheart, who bought the narrative that Beaumont’s interest in the darkness was to preserve the light. Similarly, Artie’s preservation of the light is a sham, and the reveal of the killer affirms this.

Jeffrey Beaumont in Blue Velvet. He convinces himself that he wants to save Dorothy Vallens and reunite her with her kid but the viewer can see he is, at once, unnerved and intrigued by the sordid underbelly occupied by Frank Booth and his pals. He willingly wanders into the darkness of this world and lets himself be consumed by it. At the film’s denouement, he can longer keep up the charade as innocent savior. Dorothy wanders naked and deranged into his home and refers to him as her “secret lover,” much to the devastation of his high school sweetheart, who bought the narrative that Beaumont’s interest in the darkness was to preserve the light. Similarly, Artie’s preservation of the light is a sham, and the reveal of the killer affirms this.

I could truly unpack the themes in this movie for days and days. It is a blessed anomaly, as Tex suggests, but solidly of its time. Other WTF movies I fondly recall from 1991 include Nothing But Trouble (a commercial stinker that goes to some truly unexpected places), If Looks Could Kill, and Mannequin Two: On the Move. However, while everyone should watch these movies at least once, none of them are half as intelligent as All-American Murder.

All-American Murder is available to stream free on Tubi and Pluto. A Blu-Ray edition is available from Vinegar Syndrome.