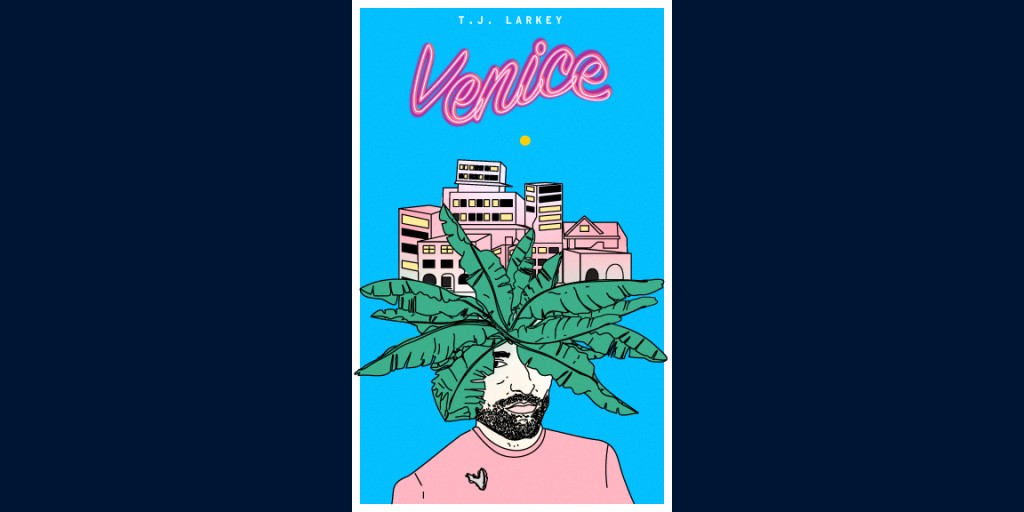

EXCERPTS FROM THE NOVEL VENICE by T.J. Larkey

Tough I’m lying on my floor, next to my bed. My bed is this big padded mat that rolls up and can be moved very easily. It’s comfortable, but I like the floor better. I believe that lying on the floor for a few hours a day will toughen me up. I was a spoiled kid, very soft, so I’m always looking for things to toughen me up. That’s how I got here. I got it in my head that moving to a big city I’d seen in movies and television, where I didn’t know anybody, would somehow make me…