Juan rose to pee in pitch darkness, his eyes fluttering. He found the toilet, but peed all over the unraised seat, splashing his shins and toes. Catching jeweled glints of chrome and glass, his eyes oriented to the darkness.

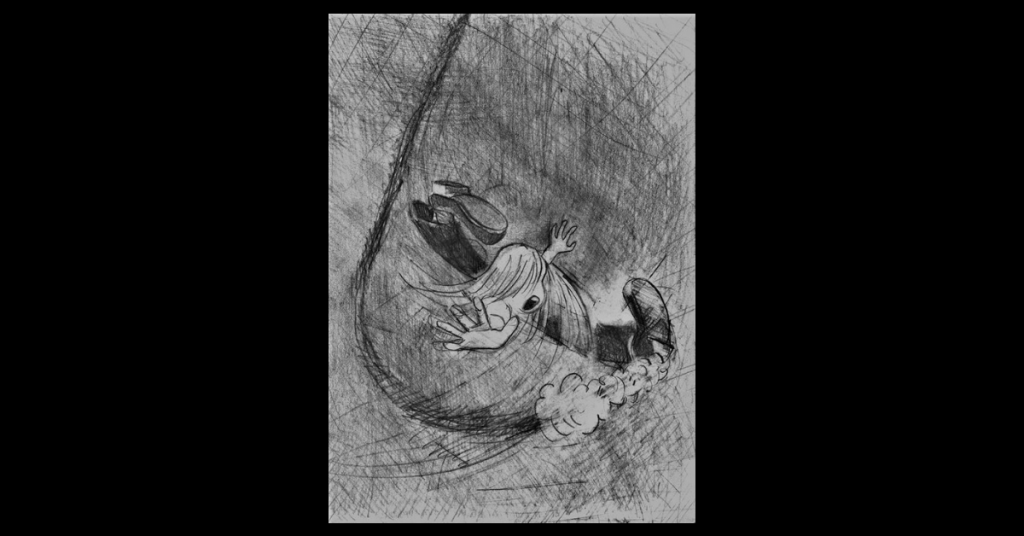

Incomprehensible, his next move—he lurched right, toward the bathtub, and not left toward the door, which led to his bedroom. The shins, bright with urine, walloped the side of the bathtub and his body pitched forward. A reflexive extension of his arms kept him from face-planting the tub.

Swollen and contused, the left shin blazed to the touch. Juan screamed and walked to the kitchen where he found an ice-pack in the freezer. It was 3:15. Thoughts of returning to sleep made him grimace. He’d need a horse tranquilizer for that.

In the living room, he switched on a lamp, and sat on the sofa, propping his left foot on the coffee table edge, next to a crystal cigarette-box that had belonged to his mother. The only remaining memento of her, all else lost or sold. He pressed the ice-pack to his left shin. The cold shock made him wince but numbed the pain.

He continued icing for a time, then got up to make coffee.

As he drank the black brew by the balcony window overlooking the courtyard, something dark and bulky fell past his balcony—bizarre, as his unit was on the topmost floor of the eight-story tenement. He stepped out on the balcony to inspect.

In the darkness—the courtyard lights long ago stoned—grainy lumps and bulges dominated. A dog barked from a recess of the courtyard. The ringing acoustics obscured the dog’s location.

After bandaging his shins, Juan dressed, took the elevator down, and limped through the shabby lobby, with its dead banana trees and ruptured red couch, and exited the front doors.

The cool, excremental air reminded him that spring was near. A time of hope. Maybe things would improve. He hobbled across the broken concrete slabs and rutted grounds of the courtyard. An almost full moon loomed behind a screen of smog, bearing a bizarre resemblance to Alfred Hitchcock. A few trees planted last spring had not survived winter and stood against the graffitied buildings in skeletal silhouette.

Juan approached the area where an object falling from the roof or sky would have landed, in respect to his balcony: nothing but clumps of sod and stone garnished with garbage. An old-fashioned sewing machine, half-buried in earth and dog excrement, drew a second glance, but its presence there preceded the incident.

He looked up. Most units were dark, but a few glowed with lamplight or flickered with the cold blue of flat-screen televisions. He surveyed the area again and, seeing nothing untoward, decided to head back.

Then, in the charcoal disorient of shadows, he detected a flicker near a concrete bench. He gingerly stepped toward it on the uneven path. When he drew closer to the bench, he observed, with a start, a pale face floating beside it, the eyes darkly luminous—apparently disembodied.

No sound issued from the face, yet it seemed to be mouthing words, or at the very least drawing breaths. He moved closer. The head wasn’t disembodied; someone was buried to the neck. Did this person fall from the roof or the sky? And land so precisely as to be buried—and still alive—up to the neck? He walked closer to the small, round head, the black hair flattened on the skull, the inky eyes gazing nowhere.

“Hey,” he said, “are you okay?”

The face continued mouthing silent words or gulping air. The dilated pupils evidenced signs of shock.

“Miss? Sir? Buddy?” Nothing. Juan stepped closer for a better look.

When he saw a thin gold hoop in the left ear, he figured it was a woman, but upon reflection decided he could not draw that conclusion: some men wore earrings. He touched the dark hair. It felt normal, perhaps sticky from product. Provoking no reaction, he let his hand fall squarely on the scalp. It was warm.

“Yo,” he said, “how did you get in this predicament?”

The head twitched, almost in irritation at the pressure of Juan’s hand, but he held it firm. A survey of the balconies revealed no peepers, at least not so far as he could tell.

He fronted the head and bent down so that his nose came close to its nose.

“Why don’t tell me what’s going on and I’ll go get you help?”

The face opened and closed its mouth, the eyes throbbed darkly, but no words emerged. It was a woman, he determined, or a man with delicate face bones. He touched the cheek. Despite the mud streaks, it felt soft and warm. Now the eyes regarded him. Perhaps the senses, after suffering a terrible shock, were slowly regathering.

“Did you fall from the roof?” he asked. “Did someone throw you?” he asked before hearing a response.

The mouth moved, but the voice box must have been blocked.

“Okay, just nod. Did you fall?”

The head nodded.

“Did someone push you?”

Again, the head nodded.

“From the roof?”

Again, the head nodded.

Using a small end of two-by-four he found by the bench, Juan dug away some of the surrounding dirt, so tightly packed around the neck it proved difficult to turn over. Sturdy shovels or machinery were needed to clear enough dirt to free the victim.

“This is unusual,” Juan stated.

The head nodded.

These days so many things defied logic and credibility that you never knew where you stood. He bent and studied the face.

The mouth spat up dirt. Juan wiped the lips with the back of his hand. He stroked the cheek. How warm to the touch, that cheek—and soft. He smiled. Then, for reasons he could never explain, he opened his hand, drew back his arm, and slapped the face hard enough to rock the head back. The sound reverberated through the courtyard.

Juan jumped up and looked at his stinging hand as if it belonged to someone else.

“I’m so sorry I did that,” he said, horrified at himself.

The dark eyes moistened. Juan felt terrible. What was he thinking? He stroked the cheek he had slapped. The eyes shut, and the face leaned warmly into his hand.

Afraid he had crossed some line, he stood up, heart racing, and headed to his building. He took the elevator up to his flat and called 911.

“911. What is your emergency?”

“Someone’s buried up to their neck in my courtyard.”

“Did you say buried up to their neck?”

“I think she fell off the roof.”

“Have you been drinking, sir?”

“I have not been drinking.”

“How do you know she fell off the roof? Did you push her?”

“I didn’t push her. I’m not sure she fell off the roof—I’m not making this up.”

The dispatcher took the address and said paramedics would be there shortly.

“Sounds like she’s in some pickle.”

“Yeah,” Juan said looking at his hand, “it’s unusual.”

He rang off. He took the elevator down to the lobby and was headed to the courtyard when he ran into the super, Mr. Greenwood, standing there with his right hand locked in an involuntary half-salute.

“Morning, Mr. Greenwood.”

“What are you doing here at this time?”

“Long story.”

Silver-haired Mr. Greenwood, mustachioed, fond of Tartan cardigans, suffered from early onset dementia. He rarely slept beyond 4 a.m. if he slept at all. His face evidenced the softening and slackening signs of gradual and irreversible stupefaction.

“I’m going to walk the dog,” he said.

Despite knowing Mr. Greenwood had no dog, Juan scoped the lobby.

“So what’re you doing here?” Mr. Greenwood said. “Up to no good?”

Juan balked. “What do you mean by that?”

Mr. Greenwood’s silver moustaches shook as he laughed. His right hand shook as well but remained raised as though in mid-salute.

“A girl’s buried up to her neck in the courtyard,” Juan said.

“Do tell,” Mr. Greenwood said.

“Dunno know how she got there.”

“Kids these days are animals.”

Smiling mirthlessly, Juan exited.

As sirens approached, he hastened his step. He wondered if someone had buried the woman to make a point. People do all kinds of crazy things to make points.

He walked to the bench, but when he looked for the buried woman, he discovered, to his chagrin, that she wasn’t there. Indeed, the hole where she’d been buried was filled in. He stood there glancing left and right. He’d been gone no longer than a few minutes.

When he stepped on the spot where the woman had been buried to her neck, the ground looked undisturbed. He glanced at the sky and its smog-dimmed Hitchcock moon and shuddered.

The sirens intensified. A dog barked. Juan’s eyes searched the courtyard, but shadows prevailed. Then, on the verge of tears, he saw something glinting in the ground. He stepped to the spot and kneeled.

He pulled a gold hoop out of the dirt, blew it clean, and held it in his palm. At that moment a flashlight beam shone in his eyes, blinding him.

“Put your hands where I can see them,” barked a voice behind the beam.

Juan raised his hands.

“Don’t fucking move,” said another voice.

Before Juan knew it, two uniformed police officers seized his arms. He demanded to know why they were manhandling him.

“Someone reported a prowler,” said the officer with the flashlight, beaming it at himself and casting a large ghoulish shadow against the tenement.

“I called 911,” Juan said. “There was a girl.”

“What girl?”

“She was buried—”

“You buried a girl?” said the other officer, tightening his grip.

“I didn’t bury her,” Juan protested. “I think she fell from the roof.”

Both officers looked at Juan.

“Where’s the girl now?” asked the officer with the flashlight.

Juan shrugged. Tears filled his eyes. He tried to exhibit the earring left behind to the officers, but they ignored him.

“Show us,” said the officer with the flashlight.

“What do you mean?” Juan said.

“Show us where the girl jumped off the roof,” said the other officer.

“Yes, take us up to the roof and show us.”

The officer with the flashlight led the way through the courtyard, the other officer close on Juan’s heels.

They passed Mr. Greenwood in the lobby.

“He’s no good,” Mr. Greenwood cackled. “He’s no good.”

“We need roof access.”

“Follow me,” Mr. Greenwood said. “And don’t mind Rexy, he don’t bite.”

The officers exchanged a glance but kept mum. They took the elevators up to the eighth floor and then walked through a door opening into a shaft with a set of metal stairs. Juan had always wondered what lay behind the door. The stairs led to the roof.

The four men stood on the roof with Alfred Hitchcock sizing them up.

The officer with the flashlight blazed it in Juan’s face. “Show us,” he said.

“But show you what?” Juan said.

Mr. Greenwood sat on a steel duct, right hand raised, whistling, as if for a dog.

“Well,” said the flash-lit officer, “if you don’t show us, maybe we’ll show you.”

“That’s a perfect idea,” said his colleague, grimacing. He removed his cap and jacket, and then slipped off his shoes and socks.

The officer with the flashlight followed suit.

Then, they faced each other in their shirts and trousers. They slapped each other on the shoulders. The officer with the flashlight turned and tossed it to Juan.

“Illuminate us,” he said.

Juan did as requested and shone the flashlight on them. They looked bloated and unhealthy. Then, the officers locked arms and in total silence leaped off the roof, down into the darkness of the courtyard.

Juan dropped the flashlight.

“Rexy,” Mr. Greenwood whispered. “Rexy. Bad dog. Bad dog.”